Why Communion on the Tongue?

Part II of II

The Passive Action of Communion

Editor’s Note: In Part I, Christopher Carstens introduced the topic of the reception of Holy Communion on the tongue. Today, in Part II of the series, he offers three considerations for receiving the Holy Eucharist in this way.

Part II: The Passive Action of Communion

An ancient maxim of the Church teaches that “the law of prayer is the law of belief” (lex orandi, lex credendi). Belief and prayer—and prayer and belief—are integrally connected to one another. We pray, for example, in the name of the Father and of Son and of the Holy Spirit because we believe that God is one substance in three persons. Similarly, our belief that Jesus is truly and substantially present in the Blessed Sacrament is deepened by humble prayer on our knees during periods of adoration (See CCC [Catechism of the Catholic Church] 1124 and Pius XII’s Mediator Dei 46-48).

This liturgical law clarifies the Church’s discipline regarding the reception of Holy Communion. Like most things liturgical—words, music, postures, time, ministers, architecture—the manner of receiving Communion should be understood and carried out in light of our belief. Our reception—whether on the tongue or in the hand—ought to reflect our Eucharistic faith and, at the same time, foster that same faith within us and in the Church.

So, what does the Church, and we as her members, believe about Holy Communion? While there are many (perhaps innumerable) dimensions to receiving the Eucharist, I find three particular notions enlightening to the question of Communion in the hand or on the tongue.

First, in Pope John Paul II’s Encyclical letter Ecclesia de Eucharistia, “On the Eucharist in its Relationship to the Church,” the late pontiff offers a remarkable comparison between the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Communicant. “There is a profound analogy,” he says, “between the Fiat which Mary said in reply to the angel, and the Amen which every believer says when receiving the body of the Lord. Mary was asked to believe that the One whom she conceived ‘through the Holy Spirit’ was ‘the Son of God’ (Lk 1:30-35). In continuity with the Virgin’s faith, in the Eucharistic mystery we are asked to believe that the same Jesus Christ, Son of God and Son of Mary, becomes present in his full humanity and divinity under the signs of bread and wine” (55). He goes on to liken Mary to a tabernacle—“the first ‘tabernacle’ in history” (ibid.).

First, in Pope John Paul II’s Encyclical letter Ecclesia de Eucharistia, “On the Eucharist in its Relationship to the Church,” the late pontiff offers a remarkable comparison between the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Communicant. “There is a profound analogy,” he says, “between the Fiat which Mary said in reply to the angel, and the Amen which every believer says when receiving the body of the Lord. Mary was asked to believe that the One whom she conceived ‘through the Holy Spirit’ was ‘the Son of God’ (Lk 1:30-35). In continuity with the Virgin’s faith, in the Eucharistic mystery we are asked to believe that the same Jesus Christ, Son of God and Son of Mary, becomes present in his full humanity and divinity under the signs of bread and wine” (55). He goes on to liken Mary to a tabernacle—“the first ‘tabernacle’ in history” (ibid.).

If there is a lesson for the communicant, it is that, like Mary, our reception of Jesus is characterized by lowliness, humility, and docility.

A second consideration of Eucharistic Communion stems from the texts of the Roman Missal. At the end of the preparatory rites prior to the Eucharistic Prayer, the priest commands us to “Pray that my sacrifice and yours may be acceptable to God, the Almighty Father.”

A second consideration of Eucharistic Communion stems from the texts of the Roman Missal. At the end of the preparatory rites prior to the Eucharistic Prayer, the priest commands us to “Pray that my sacrifice and yours may be acceptable to God, the Almighty Father.”

This notion of sacrifice, says Pope Benedict, is “a concept that has been buried beneath the debris of endless misunderstandings” (The Spirit of the Liturgy 27). While it is tempting to think of “sacrifice” as essentially pain, loss, suffering, and deprivation, at its heart sacrifice is union with God, divinization, and “becoming love with Christ” (76).

Consequently, if Eucharistic Communion is the fruit of Christ’s—and our own—sacrifice, that is, his action of selfless turning to the Father, our manner of reception likewise needs be characterized by our heartfelt desire to unite to God our entire freedom, memory, will, and all we possess (“Prayer of Self-Offering,”* St. Ignatius of Loyola, found in the Roman Missal).

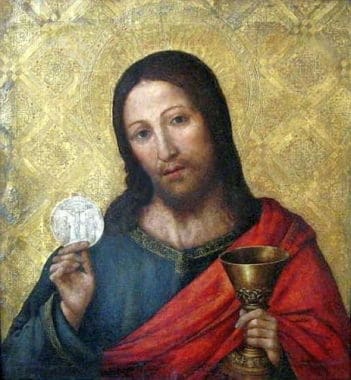

Finally is the amazing insight of St. Augustine. Recounted by Pope Benedict in his exhortation Sacramentum Caritatis, “Augustine imagines the Lord saying to him: ‘I am the food of grown men; grow, and you shall feed upon me; nor shall you change me, like the food of your flesh, into yourself, but you shall be changed into me.’ It is not the Eucharistic food that is changed into us, but rather we who are mysteriously transformed by it” (70).

Finally is the amazing insight of St. Augustine. Recounted by Pope Benedict in his exhortation Sacramentum Caritatis, “Augustine imagines the Lord saying to him: ‘I am the food of grown men; grow, and you shall feed upon me; nor shall you change me, like the food of your flesh, into yourself, but you shall be changed into me.’ It is not the Eucharistic food that is changed into us, but rather we who are mysteriously transformed by it” (70).

If we believe that this “mysterious food” (ibid.) has the power to change us—if we believe as St. Augustine and Pope Benedict believe—our manner of eating must signify such belief. Eucharistic food is “not something to be grasped at” but is received with humility and obedience (Phil 2:7-8). Only then will we be, like Christ, “highly exalted” (Phil 2:9).

The three above reflections offer a number of common elements relative to Eucharistic Communion: humility, docility, fidelity, selflessness. Which manner of receiving (the lex orandi) best expresses and fosters these truths (the lex credendi)?

Even though, as Pope John Paul acknowledges, Communion in the hand can be carried out with reverence and devotion; and even though reception on the tongue is no guaranteed symbol of fidelity and humility; Communion on the tongue is, all things being equal, the most suitable manner of reception.

In certain cultures, including our own, the bride and groom often receive from the hand of the other a piece of wedding cake at the wedding banquet. When done with love and devotion and faithfulness, the small gesture signifies not only the care one pledges to the other, but also the concern a vulnerable spouse can expect from the other. At the Wedding Feast of the Lamb, our humble reception of the fruits of his saving work likewise show our devotion to him, our Spouse, and express our abandonment into his care.

+

Christopher Carstens is Director of the Office for Sacred Worship in the Diocese of La Crosse, Wisconsin, instructor at Mundelein’s Liturgical Institute, and editor of the Adoremus Bulletin.

+

*The Prayer of Self-offering (commonly known as the Suscipe) of Saint Ignatius of Loyola can be found on page 1484 of the Roman Missal by clicking here.

+

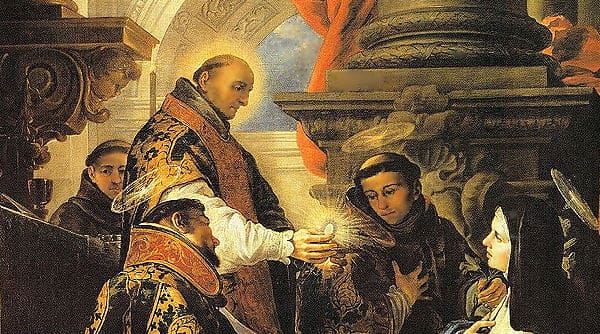

Art: Saint Joseph’s Catholic Church (Central City, Kentucky) – stained glass, portal tympanum detail, I AM the bread of life, Nheyob own work, 6 June 2014, CCA-SA 4.0 International; Modified detail of The Annunciation, Bicci di Lorenzo, circa 1430, PD-US author’s life plus 100 years or less; La [última] comunión de Santa Teresa (The (last) communion of Saint Teresa), Juan Martín Cabezalero, circa 1670, PD-US author’s life plus 100 years or less; Christ with the Host, Paolo de San Leocadio, 4th quarter of 15th century, PD-US author’s life plus 100 years or less; all Wikimedia Commons.