Life, As I Find It

Inasmuch as my life is still consumed with projects related to C.S. Lewis, I’ve been thinking about a little-known aspect of his life: the penalty he paid for being an outspoken Christian.

In the 1940’s, while Lewis became a best-selling author, lecturer and broadcaster, his co-workers at Oxford University were not pleased. For them, Lewis had broken an unwritten code by talking publicly about his faith. Not because they were specifically anti-Christian – though many were – but because it was considered unseemly. J. R. R. Tolkien once told Lewis scholar Walter Hooper that Oxford dons could be forgiven for just about anything except writing outside of their subjects or “writing popular works of theology.”

As early as 1933, when Lewis wrote The Pilgrim’s Regress, his fellow academics belittled him for daring to write openly about something as personal as his faith (or maybe they were annoyed because his book satirically attacked their philosophical views). Their consternation increased seven years later with the release of The Problem of Pain, in which Lewis tackled the subject of suffering from a layman’s point of view. Next came The Screwtape Letters, his very wry and insightful look at temptation from a demon’s point of view, which lambasted many of their cherished ideas. Then the BBC enlisted him to voice a series of talks about Christianity, which later became the book Mere Christianity. It was overtly evangelistic which, for his colleagues, was even worse than the others. It was one thing to write dispassionately, it was another thing to try to persuade people to one’s faith.

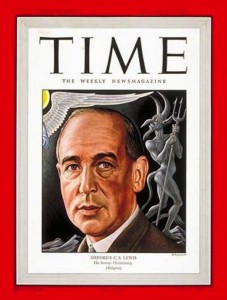

In 1947, Time magazine did a cover story on Lewis – the reporter calling him a “heretic” among academics for daring to believe in God. That reporter got it right. Some professors accused Lewis of having a religious mania.

In 1947, Time magazine did a cover story on Lewis – the reporter calling him a “heretic” among academics for daring to believe in God. That reporter got it right. Some professors accused Lewis of having a religious mania.

Lewis had been teaching at Oxford since 1925. As late as 1951, he was outvoted for Oxford’s prestigious Poetry Chair by 194 votes to 173. Lewis’ older brother Warnie noted in his diary how surprised he was by the “virulence of anti-Christian feeling” toward Lewis at Oxford. Warnie was informed that one elector had voted against Lewis simply because he’d written The Screwtape Letters.

On one occasion, after being warned that his Christian writings would destroy his academic career, Lewis quoted General William Booth of the Salvation Army, who had famously proclaimed: “If I could win one soul for God by playing the tambourine with my toes, I’d do it.”

According to a colleague, that was precisely what some people thought Lewis was doing.

Yet Lewis persevered even while being passed over again and again for advancement at Oxford. He was not given a full professorship until he left that university for Cambridge in 1954, almost 30 years after his career began.

Like C.S. Lewis, we live in an age when great pressure is put upon us for daring to proclaim our faith publicly. Every day our families, our friends, our adversaries, even total strangers, will vilify us for standing up for the Truth. We will be derided for putting that Truth ahead of relationships. We may be held back professionally for refusing to keep our mouths shut, for not compromising or capitulating. We will be treated as Neanderthals for believing the impossible – that God became Man, died for us and then conquered death so that we could have new lives in Him. We will be declared moronic for speaking the unspeakable – that Jesus calls us away from our cultural narcissism and expects us to sacrifice ourselves, our passions, our plans, our all, to follow Him.

Until now, it hardly seemed possible that we might actually have to do it.

Are we ready?

Are we willing?