Mini-Course on Prayer:

Part 2: Listen to St Teresa of Avila

Editor’s Note: In Part 1, David Torkington introduced us to the unquenchable fire of love. Today, he will talk about St Teresa of Avila’s wisdom regarding how to go forward in prayer.

Making the spiritual ascent into God is rather like trying to run up a downward escalator. The moment you stop moving steadily forwards is the moment when you start moving steadily downward.

Going steadily forwards means finding daily time to do what St Peter told his listeners to do when he was the first to announce the good news that God’s love had just been unleased on the first Pentecost Day. He told them to keep turning and opening themselves to God’s love every moment of their lives. Speaking to them in languages they could understand, he used the word ‘repent’. In Hebrew there is no such word for someone who has repented, but only for someone who is repenting. It is a continuous on- going process that pertains to the very essence of the Christian life. This repenting or this turning and opening oneself to receive the love of God has to be learnt, and the place where it is learnt has traditionally been called prayer. That is why there is nothing more important in our lives than prayer, because without it we cannot receive the only love that can make us sufficiently perfect to enter into the life of the Three in One to which we have been called. That is why St Teresa of Avila said, “There is only one way to perfection and that is to pray; if anyone points in another direction then they are deceiving you.” There is nothing therefore more important than prayer.

going process that pertains to the very essence of the Christian life. This repenting or this turning and opening oneself to receive the love of God has to be learnt, and the place where it is learnt has traditionally been called prayer. That is why there is nothing more important in our lives than prayer, because without it we cannot receive the only love that can make us sufficiently perfect to enter into the life of the Three in One to which we have been called. That is why St Teresa of Avila said, “There is only one way to perfection and that is to pray; if anyone points in another direction then they are deceiving you.” There is nothing therefore more important than prayer.

When human beings love their love is both physical and spiritual, but as God has no body his love is entirely spiritual. As a mark of respect we have come to call his love the Holy Spirit. As we keep turning and opening ourselves to receive the Holy Spirit in prayer, he continually draws us up like a supernatural magnet into Christ and then, in, with and through him into the life of the Three in One, to contemplate and enjoy the Father’s love to all eternity.

Many years ago I was privileged to attend a retreat given by Cardinal Hume. After agreeing with St Teresa he went on to define exactly what he meant by prayer. He first quoted and then slightly modified the definition given in what used to be called the old penny Catechism. “Prayer,” he said is “trying to raise the heart and mind to God.” The word he introduced to the old definition was ‘trying’, to emphasise that the essence of prayer is in the trying.

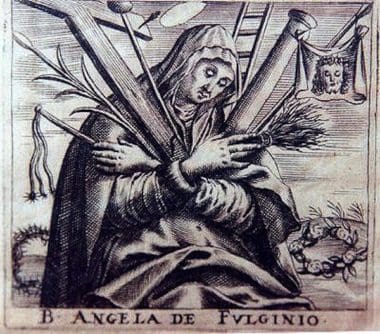

The quality of our prayer is ultimately determined by the quality of our endeavour. It was for this reason that the great mystic and mother, [Saint] Angela of Foligno said that prayer is, “The school of divine love.” In other words, it is the place where we learn how to love God by daily trying to raise our hearts and minds to him. I intend to introduce you to the different means and methods that tradition has given us to help us to keep trying to turn and open our minds and hearts to God in this little series, but first let me say this. There are no perfect means to help us keep trying to raise the heart and mind to God, just different means. What helps you at the beginning, may not help you later on. What helps you in the morning may not help you in the evening What helps me, might not help you. Remember the famous words of Dom John Chapman, “Pray as you can and not as you can’t.” The acid test is, does this means of prayer help me to keep trying to keep raising my heart and mind to God?

One thing I will promise will happen when you seriously set aside some daily space and time for prayer. You will find that no matter what means of prayer you choose to use, you will be deluged by distractions. After a few weeks of distractions and temptations buzzing around in the head like a hornet’s nest, many people come to the conclusion that they cannot pray. They then tend to pack up giving a special time for prayer, and only turn to God in extremis when they are in trouble. Here is the secret of prayer that has to be learned from the outset. The very distractions that you think are preventing you from praying are the very means that enable you to pray. That is why St Teresa of Avila said that you cannot pray without them. Each time you turn away from a distraction to turn back to God, you are in fact performing an act of selflessness; you are saying no, to self and yes, to God. If in fifteen minutes you have a hundred distractions, it means that one hundred times you have made one hundred acts of selflessness. Gradually, if you continue to do this day after day, then acts of selflessness lead to a habit of selflessness that helps you to pray better and better. That is why  [Saint] Angela of Foligno said that prayer is the School of Love where loving is learnt by practising selfless loving. If you have many distractions and you keep turning away from them, then you will get straight A’s when the examination comes round. If, however, you only have two – one is dreaming about where you are going for your next summer holiday and the next is worrying about how to get the money to get there, then that is a different matter. Let us suppose that when you settle down to pray you fall asleep. Is that prayer? No. On the other hand, let us suppose that the moment you are preparing to pray you are swept up into an ecstasy. Is that prayer? No. In the first case you were doing nothing, and in the second case God was doing everything. Strictly speaking you were not praying at all in either case. Prayer is what happens between the sleep and the ecstasy where you are continually trying to raise your heart and mind to God, and in so doing learning how to love in the School of Divine Love.

[Saint] Angela of Foligno said that prayer is the School of Love where loving is learnt by practising selfless loving. If you have many distractions and you keep turning away from them, then you will get straight A’s when the examination comes round. If, however, you only have two – one is dreaming about where you are going for your next summer holiday and the next is worrying about how to get the money to get there, then that is a different matter. Let us suppose that when you settle down to pray you fall asleep. Is that prayer? No. On the other hand, let us suppose that the moment you are preparing to pray you are swept up into an ecstasy. Is that prayer? No. In the first case you were doing nothing, and in the second case God was doing everything. Strictly speaking you were not praying at all in either case. Prayer is what happens between the sleep and the ecstasy where you are continually trying to raise your heart and mind to God, and in so doing learning how to love in the School of Divine Love.

These ideas are developed further in my two major works on prayer – Wisdom from the Western Isles and Wisdom from the Christian Mystics.

Editor’s Note: In Part 3, David Torkington will talk about what happens when we give ourselves to God in prayer.

+

Art for this post on listening to St. Teresa of Avila: Mirror of Teresa of Avila, Peter Paul Rubens, 1615, CCA-SA 3.0 Unported; Angela de Foligno, unidentified author, XVIIth century print, PD-US author’s life plus 70 years or less; both Wikimedia Commons.