On the Importance of Silence in the Liturgy*

By Cynthia Trainque

Many Catholics rightly complain about the absence of silence in…the celebration of our Roman liturgy. It is…important, therefore, to recall the meaning of silence as a Christian ascetical value, and therefore as a necessary condition for deep, contemplative prayer, without forgetting the fact that times of silence are officially prescribed during the celebration of the Holy Eucharist, so as to highlight the importance of silence for a high-quality liturgical renewal.

Indeed. Catholics do “rightly complain” about the lack of silence at Mass because silence is both a form of prayer in itself and it is also the opening one needs in order to pray.

1. Silence as a Christian Ascetical Value — Personal Prayer

You may be wondering, Just what is asceticism? Isn’t that some necessary thing for monks and nuns who hardly get to see much beyond their own monastic enclosures? What does that have to do with the average person in the pew?

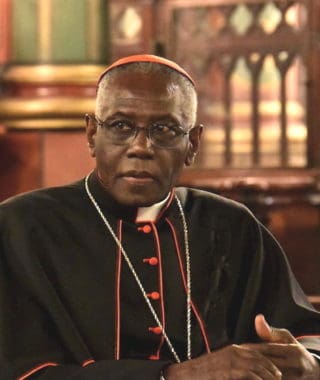

According to His Eminence Cardinal Robert Sarah, the [71-year-old] Prefect of Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments (one of the offices within the Roman Curia) wrote this in his essay, Silence in the Liturgy, published in Italian in L’Osservatore Romano on January 30, 2016:

According to His Eminence Cardinal Robert Sarah, the [71-year-old] Prefect of Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments (one of the offices within the Roman Curia) wrote this in his essay, Silence in the Liturgy, published in Italian in L’Osservatore Romano on January 30, 2016:

Asceticism is an indispensable means that helps us to remove from our life anything that weighs it down, in other words, anything that hampers our spiritual or interior life and therefore is an obstacle to prayer. Yes, it is indeed in prayer that God communicates his Life to us, in other words, manifests his presence in our soul by irrigating it with the streams of his Trinitarian Love: the Father through the Son in the Holy Spirit. And prayer is essentially silence.

One must practice coming to that necessary silence in order to be receptive to the seed of God’s word…it must find that place of “good soil” where it can “produce a crop.” It matters not whether that seed is as a “mustard seed” for we know that it grows into one of the largest of bushes. Personal silence of this sort is vital for those times in the Liturgy where silence is a response to God’s word. All of the great saints were great prayers…or became great prayers. Not all began their journeys as masters of prayer. Many struggled with it for years. St. Teresa of Avila and others wrote books on it.

2. Silence is a Necessary Condition for Deep, Contemplative Prayer

Silence is necessary as a form of prayer itself. It is a searching for and a response to the Living God. If I enter into prayer, of what good is my endless prattle if I am never quiet to hear God’s reply? If one spouse of a married couple talks endlessly to the other, how will s/he hear the reply of the other? The same is said for the great “conversation” between God and the individual at Liturgy. The worship of the Father in and through the Son by the power of the Holy Spirit is an act so holy that it demands times of silence — the silence of adoration, the silence of contentment, the silence of profound awe. Silence is an act of love…it is total receptivity. The individual — the soul — is made for God like a flower pot is made for growing plants. Plants grow in silence and their very beginnings are hidden deep within the “womb” of the rich soil. Silence changes us. We need the sacred “action” of silence.

Returning to the above-mentioned article by Cardinal Sarah, he says this about silence as a condition for contemplative prayer:

The Gospels say that the Saviour himself prayed in silence, particularly at night (Lk 6:12), or while withdrawing to deserted places (Lk 5:16; Mk 1:35). Silence is typical of the meditation by the Word of God; we find it again particularly in Mary’s attitude toward the mystery of her Son (Lk 2:19, 51). The most silent person in the Gospels is, of course, Saint Joseph; not a single word of his does the New Testament record for us.

Didn’t Mary “ponder these things in her heart”? Perhaps Mary was not at synagogue or at some level of formal prayer when the Angel Gabriel appeared to her — but she was at deep silent prayer. One who has been schooled in the ways of God can easily enter into prayer even whilst sweeping the floor or spinning wool into yarn. St. Paul exhorts us to “Pray without ceasing.”

3. Silence as an Important Component of the Liturgy

All parishes should allow for silence in the Church as soon as one enters into it, for to enter into a Catholic Church is to pull back the door into heaven itself. But alas, too many churches are more and more like meeting places of gossip and idle chit-chat before Mass. Yet most priests fail to address the issue of silence in their churches. To speak up — even politely — to people in the parish is to be met with consternation and a look of bewilderment as well as the typical response that “Mass hasn’t started yet”…or “Mass is over”. They fail to give any acknowledgment that Jesus is still present in the reserved Eucharist. Thus Mass is often reduced to somewhat of a show. On the door to the Monastery of the Sisters of the Precious Blood in Manchester, N.H. is a sign which says, “For the sake of Jesus present in the tabernacle kindly maintain silence in this place”. One priest I know plays a CD of quiet music while the people gather — usually something calming and repetitive such as that put forth by the community of Taize. It is played at a volume that is very low.

In the Old Testament the (minor) prophet, Habakkuk declared to the people of ancient Israel in his oracle of the same name: “the LORD is in his holy temple; silence before him, all the earth!” The prophet Zephaniah likewise calls for silence: “Silence in the presence of the Lord GOD!…Yes, the LORD has prepared a sacrifice…”. If these two prophets called for silence before the presence of God how much more should we, the people of the New Testament, be silent before Jesus present in the tabernacle — Body, Blood, Soul & Divinity.

In his article, Silence at Mass, David Philppart describes silence as “akin to these: the silence that gestates between people who know and love each other so well that words are not always necessary; the awe-filled silence evoked by an encounter with beauty; the calm quiet that befalls those who gaze, listen or touch with their hearts as well as with their eyes, ears and hands.”

Further in the same article he says,

“The liturgy’s silence is communal. The assembly keeps a communion of quiet. Each one tries to the best of his or her ability to be still, but it is more than just a bunch of individuals not saying or doing anything coincidentally. It is the Body of Christ listening for and attending to the voice of God.”

And again,

“Silence in the liturgy is silence kept on purpose. It is deliberate and therefore active. It’s not an interlude, not an intermission, not an interruption of the action. At its time, it is the action: We keep the silence. ‘Be still and know that I am God,’ the psalmist sings. Silence in the liturgy is the active attending to God that Samuel showed when, upon being awakened from his sleep by the voice of God, he replied, ‘Here I am: I come to do your will,’ and then stood quietly before the Divine.”

[box type=”bio”] ![]() Cynthia Trainque is an author who is enrolled in the Master of Arts in Ministry (MAM) for the Laity at St. John’s Seminary, Brighton, MA. She has served the church for several years as a worker, writer, and volunteer and is presently an active member of St. Mary’s Parish in Ayer, MA. Cynthia is available to come to speak as a guest speaker/teacher on the beauty of the Catholic faith. She gives talks and also creates/uses PowerPoint presentations. She may be contacted at Catherineofsienamedia@yahoo.com. [/box]

Cynthia Trainque is an author who is enrolled in the Master of Arts in Ministry (MAM) for the Laity at St. John’s Seminary, Brighton, MA. She has served the church for several years as a worker, writer, and volunteer and is presently an active member of St. Mary’s Parish in Ayer, MA. Cynthia is available to come to speak as a guest speaker/teacher on the beauty of the Catholic faith. She gives talks and also creates/uses PowerPoint presentations. She may be contacted at Catherineofsienamedia@yahoo.com. [/box]

+

Originally published in Catholic Exchange. Used with permission.

+

Art: Modified detail of Notre-Dame altar apse, ThePromenader, 30 August 2013 own work; Mirror of modified Le Cardinal Robert Sarah (Cardinal Robert Sarah), François-Régis Salefran, 5 March 2015, own work, CCA-SA; both Wikimedia Commons. Picture of Cynthia Trainque used with permission of Catholic Exchange.