Choosing Material for Meditation

How to Pray – Part III

In this series, we have seen that the Church and the saints urge us to meditate on Sacred Scripture. We have distinguished between Christian meditation (which is meditating on or pondering something) and Eastern forms of meditation (which seeks altered states of consciousness, a state of “no-thought”). Today I want to help you chose material to meditate on.

Recently a friend asked me, “Do I have to use the Gospels for meditation, or is another passage of Scripture suitable?” She felt drawn toward meditating on the Acts of the Apostles.

Almost any Scripture passage provides a good basis for meditation. I say “almost any,” because some passages of the Book of Numbers, for example, might not yield much fruit. Ancient Israelite census data is not relevant to our spiritual lives. But the Acts of the Apostles provides excellent material for meditation. It can give direction and encouragement to those involved in re-evangelizing a world that has lost sight of Christ.

At a retreat I was leading for homeschool moms a few weeks ago, a woman asked a related question about meditation. What if you find the Gospels difficult to understand? Should you meditate on something else instead? In other words, what is the best material for beginners?

Now, I suspect that most of us, having heard the Gospel stories since we were children and listened to countless homilies, can understand them well enough to benefit our prayer time. But we all have different aptitudes and different levels of knowledge.

We should not confuse meditation with Bible study. I love to study the Bible, but I do deep study outside of my prayer time. Mental prayer is not primarily concerned with increasing our knowledge of facts, but with increasing our experiential knowledge of God and consequently our love for Him. In other words, the historical context of our chosen passage, the precise meaning of the original Greek or Hebrew words, or the geography of the Holy Land can aid in our understanding of Scripture, but are not essential for prayer. In praying with Scripture, we focus on God’s character and will. We learn from the obedience or disobedience of our forbears. Then we examine our lives in light of what we have learned and we converse with God about it.

We should not confuse meditation with Bible study. I love to study the Bible, but I do deep study outside of my prayer time. Mental prayer is not primarily concerned with increasing our knowledge of facts, but with increasing our experiential knowledge of God and consequently our love for Him. In other words, the historical context of our chosen passage, the precise meaning of the original Greek or Hebrew words, or the geography of the Holy Land can aid in our understanding of Scripture, but are not essential for prayer. In praying with Scripture, we focus on God’s character and will. We learn from the obedience or disobedience of our forbears. Then we examine our lives in light of what we have learned and we converse with God about it.

For most people, I do recommend the Gospels as the starting place. Nowhere in the Bible or the writings of the saints do we come face to face with God as powerfully as in the Gospels. Jesus reveals the face of God to us. Every event in His life teaches us who God is and who we are.

St. Teresa of Ávila urged her nuns, no matter what stage of the spiritual life they found themselves at, to cling to Christ’s humanity. She wrote:

“[T]he last thing we should do is to withdraw of set purpose from our greatest help and blessing, which is the most sacred Humanity of Our Lord Jesus Christ. I cannot believe that people can really do this; it must be that they do not understand themselves and thus do harm to themselves and to others…. For the Lord Himself says that He is the Way; the Lord also says that He is light and that no one can come to the Father save by Him; and ‘he that seeth Me seeth my Father.'” (Interior Castle VI, 7)

If you wish to stay close to Jesus, I see no better beginning for our mental prayer than the Gospels.

If you really struggle with understanding the Gospels, you may try using the Navarre Bible. This Bible is published by book (the Gospels and Acts comprise one volume). While the commentary does have plenty of historical and contextual information, it focuses on spiritual growth. Just don’t get bogged down in all the information.

I also recommend the Psalms as a great source of meditation for beginners. The psalmists express their joys, fears, triumphs, failures, doubt, trust, and the gamut of human experience in beautiful, poetic prayer. The Psalms are relatively easy to understand. We easily pass from reading them to praying them, then expressing our own inmost feelings to God.

Here are a few other suggestions for choosing material:

Instead of playing “Bible Bingo,” randomly opening Scripture and expecting God to speak to you through it, I recommend systematic reading. Try praying through one book from beginning to end. The Bible is easier to understand when passages are read in context. You might notice themes that carry over from one day’s meditation to the next. These themes can guide your spiritual life.

Another method starts with a theme. Each day you read a separate passage that touches on the chosen theme. The passage could be from anywhere in the Bible. The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius, and prayer books based on it, epitomize this method. I am currently using this method under spiritual direction. I find the concentration on one virtue for several weeks fruitful for my spiritual life. You can even choose your own themed passages with a topical concordance.

Fr. Tim Gallagher’s An Ignatian Introduction to Prayer provides simple, Scripture-based meditations for beginners. Each one leads the reader through a short Bible passage, using a standard format. After reading the book, you should be able to continue praying on this way on your own.

What about using nonbiblical material for meditation? Books of meditations, of varying quality and orthodoxy, abound. The inexperienced person may find such books helpful, but most faithful practitioners will probably quickly outgrow them. Of course, meditation comes easier for some people than others. Don’t feel ashamed if you still need to rely on a book of meditations after years of practice.

One excellent, classic source for learning to meditate is Introduction to the Devout Life by St. Francis de Sales. St. Francis teaches a meditation method. He leads the reader through several sequential meditations on the spiritual life, in a manner reminiscent of St. Ignatius. Not only is St. Francis’s orthodoxy certain, his meditations are geared toward helping you reach the heights of the spiritual life. One problem I find with many other books of meditations is that they give no hint of a call to deeper prayer or a more mature spirituality. St. Francis wrote for lay people, to teach us how to become saints. He challenges us to keep moving forward.

Your spiritual director, if you have one, should be able to recommend meditation material for you. If you lack a director, ask friends or family members who have a firmly established prayer life what works for them.

Remember, true prayer is an intimate conversation with God through Christ. All prayer methods should focus on nurturing this relationship, using the mind and heart to draw nearer to God as long as we can. Sacred Scripture, the Gospels in particular, provides the best material for that conversation.

+

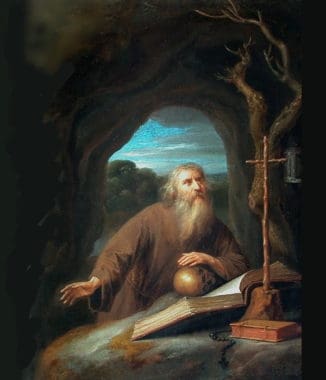

Art for this post on choosing material for meditation: Modification and partial restoration of Saint Jérôme en prière dans une grotte (Saint Jerome in Prayer in the Cave), Pieter Cornelisz van Slingelandt, 1656, PD-US author’s life plus 100 years or less, Wikimedia Commons.