Sins of Ignorance and Sins of the Flesh

Editor’s note: It is our great pleasure to welcome Father Brian Mullady OP to our writing team. He is a professor, preacher and retreat master, who has authored three books, and is the Theological Consultant to the Institute on Religious Life. Please welcome him warmly and make him feel at home!

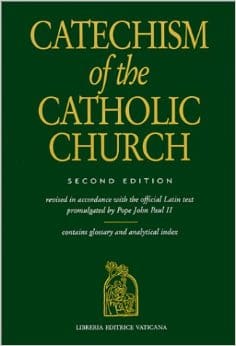

It is a moral truth that “if we don’t know something is wrong, it may remain a moral evil, but we cannot be held accountable for sin. The very fact that we do what we know to be wrong is what makes it a sin.” This is because the three requirements for a mortal sin which are stated well in the Catechism of the Catholic Church paragraph 1857: “For a sin to be mortal, three conditions must together be met: “Mortal sin is sin whose object is grave matter and which is also committed with full knowledge and deliberate consent.” The requirement of full knowledge is a serious one. But many people ask if this is not akin to saying the ignorance is bliss and not knowing the law of God is a good thing.

It is a moral truth that “if we don’t know something is wrong, it may remain a moral evil, but we cannot be held accountable for sin. The very fact that we do what we know to be wrong is what makes it a sin.” This is because the three requirements for a mortal sin which are stated well in the Catechism of the Catholic Church paragraph 1857: “For a sin to be mortal, three conditions must together be met: “Mortal sin is sin whose object is grave matter and which is also committed with full knowledge and deliberate consent.” The requirement of full knowledge is a serious one. But many people ask if this is not akin to saying the ignorance is bliss and not knowing the law of God is a good thing.

The solution to this seeming dilemma is solved if one studies attentively the teaching of Thomas Aquinas. In his Summa Theologiae, St. Thomas  establishes the requirement for a moral act. The act must proceed from deliberate will. This does not determine whether it is good or evil. That is a separate consideration. The intellect enlightened by the divine and natural law determines that. This rather determines if the will is present in an act which in turn fixes moral responsibility.

establishes the requirement for a moral act. The act must proceed from deliberate will. This does not determine whether it is good or evil. That is a separate consideration. The intellect enlightened by the divine and natural law determines that. This rather determines if the will is present in an act which in turn fixes moral responsibility.

Since knowledge, especially of a circumstance, does affect the consent of the will, St. Thomas asks if ignorance renders an act involuntary and thus not responsible. He makes a distinction between an ignorance which comes before the act of the will and which the will cannot alter and ignorance which follows the act of the will and the will of the person cannot alter.

The first would be an example of invincible ignorance. An example, a man who is hunting in a forest, hears a noise and does what all hunters are morally obliged to do to determine if there is a man there. He shoots and kills a man and is not held responsible for this deed. The hunter did all that morals obligated him to do in hunting to inform his conscience.

Sins caused by consequent ignorance result from what is known as vincible ignorance, when someone either: purposely does not want to know, so he can more easily sin, or neglects to find out what the duties of his state demand he know before he acts. For example, a man is hunting in a forest, hears a noise, and does nothing hunters are to do to resolve his ignorance as to whether he would be shooting a man or an animal, and shoots and kills a man. He is guilty of murder. Not cold-blooded premeditated murder, but murder nonetheless. His action is more willing because of his callous indifference towards human life.

This principle is applied to the conscience. A person has a moral obligation to form a correct and certain conscience before acting. This means he must take all the means necessary for him to know  the truths of his actions. The light of reason and revelation are the correct means. As a result of the ignorance we still inherit from the original sin, though natural law is engraved on the conscience of each man, many wander in ignorance about sin, which is why God had to resolve this by his law. If a man has done all that is in his power to resolve his ignorance then, though he may commit a sin, he is not responsible for the evil which remains an evil. If on the other hand, he has neglected to learn what he could and should know, then he is responsible.

the truths of his actions. The light of reason and revelation are the correct means. As a result of the ignorance we still inherit from the original sin, though natural law is engraved on the conscience of each man, many wander in ignorance about sin, which is why God had to resolve this by his law. If a man has done all that is in his power to resolve his ignorance then, though he may commit a sin, he is not responsible for the evil which remains an evil. If on the other hand, he has neglected to learn what he could and should know, then he is responsible.

Vatican II and the Catechism both give examples of the sources of vincible ignorance for which a person may be held responsible. CCC paragraph 1791 states: “This ignorance can often be imputed to personal responsibility. This is the case when a man ‘takes little trouble to find out what is true and good, or when conscience is by degrees almost blinded through the habit of committing sin.’ In such cases, the person is culpable for the evil he commits.” And in CCC 1792, it says: “Ignorance of Christ and his Gospel, bad example given by others, enslavement to one’s passions, assertion of a mistaken notion of autonomy of conscience, rejection of the Church’s authority and her teaching, lack of conversion and of charity: these can be at the source of errors of judgment in moral conduct.” The quotation in 1791 is taken directly from Vatican II, Gaudium et Spes, 16.

Vatican II and the Catechism both give examples of the sources of vincible ignorance for which a person may be held responsible. CCC paragraph 1791 states: “This ignorance can often be imputed to personal responsibility. This is the case when a man ‘takes little trouble to find out what is true and good, or when conscience is by degrees almost blinded through the habit of committing sin.’ In such cases, the person is culpable for the evil he commits.” And in CCC 1792, it says: “Ignorance of Christ and his Gospel, bad example given by others, enslavement to one’s passions, assertion of a mistaken notion of autonomy of conscience, rejection of the Church’s authority and her teaching, lack of conversion and of charity: these can be at the source of errors of judgment in moral conduct.” The quotation in 1791 is taken directly from Vatican II, Gaudium et Spes, 16.

Regarding sins of the flesh which result from passion, St. Thomas is also clear that sins of passion are of more shame but less responsibility than those which result from deliberate will. The same principle would apply here as in ignorance. If the passion comes before the act of the will and takes it by surprise then it is less willing. If after, it make the act is more willing.

This does not mean sins of the flesh are unimportant, just that all things being equal they are not as grave as sins of the spirit. However, St. Thomas also is clear that one must take them very seriously because they are the first place where the moral life and conscience begin to be corrupted. The sad example today is internet pornography which afflicts many otherwise devout Catholic men and should be taken very seriously as a place where moral life must be strengthened to pursue virtue.

Fr. Brian Mullady, O.P., STD

+++++++

Art/Photography: Fr. Brian Mullady, used with permission. Saint Thomas Aquinas, Adam Elsheimer, 1604, PD-US author’s life plus 100 years or less; mirror of Thomas von Aquin [Thomas Aquinas], Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510), unknown date, PD-US published in the U.S. prior to January 1, 1923, author’s life plus 100 years or less; both Wikimedia Commons. Catechism of the Catholic Church, file copy.