Life, As I Find It

In 1843 Charles Dickens was in trouble. After writing a series of best-selling novels – The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, and Nicholas Nickleby, he had seen a down-turn in his popularity. The serialized The Old Curiosity Shop had proven controversial due to the heart wrenching death of a main character, Barnaby Rudge and Martin Chuzzlewit simply didn’t capture the interest of his readers (the latter alienating American readers because of its satirical view of their country). He was struggling financially, due to bad business dealings, a growing family, and increasing debt. He was anxious to create a story that would touch readers the way he had before. To put it in modern terms: he needed a hit.

In 1843 Charles Dickens was in trouble. After writing a series of best-selling novels – The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, and Nicholas Nickleby, he had seen a down-turn in his popularity. The serialized The Old Curiosity Shop had proven controversial due to the heart wrenching death of a main character, Barnaby Rudge and Martin Chuzzlewit simply didn’t capture the interest of his readers (the latter alienating American readers because of its satirical view of their country). He was struggling financially, due to bad business dealings, a growing family, and increasing debt. He was anxious to create a story that would touch readers the way he had before. To put it in modern terms: he needed a hit.

Dickens was enigmatic spiritually. He was an Anglican in the populist sense, had dabbled with Unitarianism, but had little patience for any religion that did not help the poor, through either indifference or incompetence. He equated Christianity with social justice. Jesus, for him, was the ultimate social worker, a miracle man who rescued the impoverished, the outcasts and the crippled. To imitate Christ in that way was true Christianity – and Dickens used his talent to that end. His novels, up to that time, had often shocked British society for their exposes of the lives of the poor and, more specifically, children. He argued for the reformation of laws to correct the appalling conditions in child labor.

It’s hard for us to imagine the horrific conditions for children in Dickens’ time. The Industrial Age brought not only new technology but a utilitarian pragmatism about business and money. Humanity was no longer a primary consideration, except as workers. Children, as young as five years old, often worked fifteen to eighteen hours a day, every day, in rat-infested shops and factories for mere pennies. The rural enjoyments of holidays like Christmas, depicted lovingly by Dickens in The Pickwick Papers, were far removed from the urban nightmare experienced in the cities.

Dickens often visited the “Ragged Schools” around London – institutions created to help impoverished children. The schools were overwhelmed and underfunded, barely able to help their pupils physically, let alone teach them anything. Dickens wrote that to “gain their attention in any way is a difficulty, quite gigantic. To impress them, even with the idea of God, when their own condition is so desolate, becomes a monstrous task.”

Not surprisingly, Dickens was invited to visit similar schools and factories in other cities. In 1943, he went north to speak in Manchester. While there, he was deeply moved by the “bright eyes and beaming faces” of the children, knowing that many would not be alive to see the end of the year. Ignorance and Want (Need) became real, living monsters, fed by the greed of the Industrial Age, and annihilating the children of England.

One evening, while walking through the streets of Manchester, an idea came to him. It was profound in its simplicity: a miserly character, the ultimate product of his time in self-interest and practical apathy, is visited by ghosts that show him his past, present and future.

Dickens returned to London quickly and was so possessed by his inspiration that he “wept and laughed and wept again, and excited himself in a most extraordinary manner in the composition.” He worked as if in a fever, rejecting appointments and foregoing all social events. By early November, 1843, his “ghostly little book” was finished. He would call it A Christmas Carol.

The novel was rush-released and became an immediate bestseller. Readers were entertained, deeply moved and enlightened. Britain’s Child Labor Laws came under intense scrutiny. Even the celebration of Christmas was revived as average families reclaimed long-lost traditions and experienced a renewed interest in the birth of the Child who reached out to the poor, allowing the blind to see and the lame to walk.

The novel was immediately adapted for stage and, over the past century, movies. There are many versions one could watch this season – from early Hollywood adaptations to The Muppets to a computer-generated Jim Carey account. My personal favorite is the 1951 version featuring Alistair Sim, who delivers the definitive performance of Scrooge as a fully human representation of his time (not a one-dimensional stereotype), formed by tragic events and misguided decisions, yet capable of redemption. His conversion is one of the most believable and joyous conversions ever captured on film. And Noel Langley’s script is so true to the spirit of the book that few people can spot where he changed scenes and dialogue to make the story work as a movie.

Dickens, as with most novelists, wrote speculatively and did not intend A Christmas Carol to be “theologically correct.” Do spirits walk the earth, tormented by their inability to help those in need? Are we truly “fettered” in death with long chains and the icons of our vices? Are there ghosts of our past, present and future who might visit us one night to correct us? Dickens himself did not necessarily believe in the spiritual reality he had created as a means-to-an-end for his story. He innovated, using familiar ideas and images lifted from both Anglican and Catholic teaching. In essence, our choices in this temporal life truly impact our eternal life.

A Christmas Carol became so much a part of the consciousness of Victorian England that when newspapers reported Dickens’ death in 1870, a little girl in one of London’s ghettos asked, “Dickens dead? Then will Father Christmas die, too?” Such was the power and influence of Dickens’ imaginative tale.

+

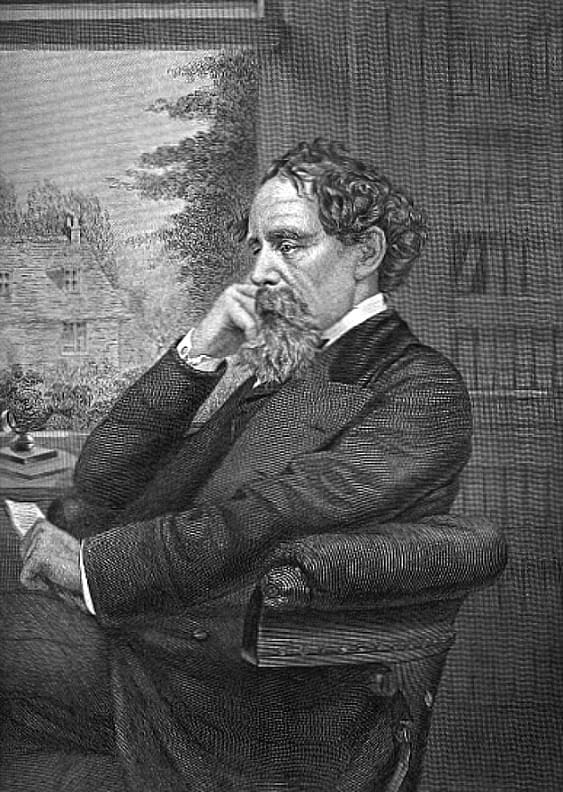

Art: Charles John Huffam Dickens (* 7. Februar 1812 in Landport bei Portsmouth, England; € 9. Juni 1870 auf Gad’s Hill Place in Rochester, England) war ein englischer Schriftsteller; from Evert A. Duyckinick: Portrait Gallery of Eminent Men and Women in Europe and America. New York: Johnson, Wilson & Company, 1873, PD-US copyright expired, Wikimedia Commons.

Editor’s Note: Paul McCusker himself dramatized and directed the audio version of A Christmas Carol for “Focus on the Family Radio Theater.”