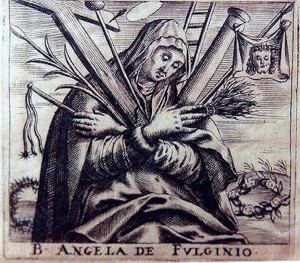

“You are I and I am you.” (Words spoken to Saint Angela di Foligno as recorded in Memorial, Chapter IX taken from Angela of Foligno: Complete Works, trans. Paul Lachance, O.F.M., in Classics of Western Spirituality, New York: Paulist Press (1993) 205.)

These are words that Saint Angela di Foligno believed the Risen Lord addressed to her. An early 14th century Franciscan Tertiary, her devotion to the humanity of Christ influenced Saint Teresa of Avila and, closer to our own time, Saint Elizabeth of the Trinity. For her, these words suggested no surmounting of the limits of  our individuality but instead a total personal presence of Christ living in the abyss our spiritual poverty, a loving presence that turns our misery into joy. It is spousal language, an expression of a tender union of love, of reverent mutual possession in faithful friendship between the Incarnate Word and the soul, the Bridegroom and His Bride – the Church. This kind of relationship with Christ moved the Franciscan widow and penitent to look on suffering, privation and even hostility of our frail humanity with love because she knew her Beloved was present in it all. She believed that when He assumed our humanity, He assumed all our poverty to Himself. Radically devoted to Him, she understood Christ’s mysterious words as an expression of tender affection, reassurance that He was entrusting the mystery of the Cross to her as His beloved so that she might “rest” in His triumphant and crucified love.

our individuality but instead a total personal presence of Christ living in the abyss our spiritual poverty, a loving presence that turns our misery into joy. It is spousal language, an expression of a tender union of love, of reverent mutual possession in faithful friendship between the Incarnate Word and the soul, the Bridegroom and His Bride – the Church. This kind of relationship with Christ moved the Franciscan widow and penitent to look on suffering, privation and even hostility of our frail humanity with love because she knew her Beloved was present in it all. She believed that when He assumed our humanity, He assumed all our poverty to Himself. Radically devoted to Him, she understood Christ’s mysterious words as an expression of tender affection, reassurance that He was entrusting the mystery of the Cross to her as His beloved so that she might “rest” in His triumphant and crucified love.

It is an error to assume that “You are I” and “I am you” refers to a mysticism of identity. Saint Angela did not really conceive of sacred humanity melting away before an abstract divine essence or the nihilistic absorption of her individuality into some super state of being or consciousness. In the spiritual practices that flow from such idealism, one cannot claim any real friendship with God. Christian prayer, on the other hand, is ordered to the most sublime of all forms of friendship — union to God in love. This is because Christian prayer is grounded in the humanity of Christ. When we affirm that Christ “assumed” our frail humanity, we do not mean He absorbed it so that it loses all meaning in some absolute. Rather, the Incarnation is a mystery by which we understand how the Word infuses impoverished humanity with new meaning, a salvific meaning in which all that is good, noble and true about humble humanity is rescued from futility.

How did she discover such devotion to Christ? Through prayer, conversion and great personal suffering. She did not start out devout. She claims to not have been very dedicated as either a mother or a wife. Yet she was visited with a special grace. She asked Saint Francis of Assisi in prayer to give her a good confessor. In a dream, the saint appeared to her and spoke to her about her way of life. In this encounter, she had a profound conversion and wanted to dedicate her life to penance. Then, disaster struck. Her husband and children all died and she was left alone in the world. Thanks to her new-found faith, rather than succumbing to despondency as one might expect, a new passion for the Lord burned in her heart and her imitation of St. Francis and his dedication to Christ’s poverty became her new pilgrim way of life.

The Franciscan penitent directs us to contemplate the humanity of Christ – a theme that lives in St. Teresa of Avila’s own doctrine of prayer. The human nature that Christ assumed to Himself is the same humanity we all share together, each in his or her own individual way. Through devotion to His humanity, Christ’s suffering shows us the truth about humanity and the sin for which we are responsible. The deepest truth is that God loves each individual person whom He has fashioned in His image and likeness. Are we ready to face how we have been indifferent to the love of God and how the absence of love in our lives has contributed to the destruction of friendship, marriage, and respect for life in the societies in which we live? The reality of this should pierce through our hard hearts until we cannot find rest in anything except that which Christ rested in – the brokenness and privation we share with one another. The Word Incarnate rested in poverty and hostility because this is where the will of the Father rests – what the Father loves, the Son loves and those whom the Lord loves, we should love.

In other words, devotion to the humanity of Christ puts us in solidarity with the poor because Jesus, in His total devotion to the Father, implicated Himself in the plight of the poor. Rather than surmounting or trying to escape poverty and weakness, this kind of devotion implicates us with the plight of those who most need God: whether they are in the womb or in hospice, whether they are mothers and fathers frightened of the gift of life or caregivers overwhelmed by the mystery of suffering and death, whether they are spouses alienated from each other or children hurting themselves for reasons they cannot understand. This is a painful, even humanly impossible place to be – but all things are possible through Christ who strengthens us. By assuming our humanity and offering to the glory of the Father on the Cross, Christ has bound Himself to all of this and so much more.

For the humble penitent of Foligno, the Incarnate Word’s faithfulness in the face of her misery and the misery of her time made her want to be like Him, the One whom she loved. Through her devotion to Christ’s sacred humanity, Saint Angela found her rest in opening her heart to the suffering of Christ in the poor – materially and spiritually – so that their plight and the plight of humanity might always pierce her heart the way it pierces the heart of God. When she speaks of resting in the Cross, she means surrendering her whole being in every moment of her life on this holy trysting place of this crucified love. Here lives that hidden fruitfulness that alone provides real hope for the world, a true new beginning. Before the words, “You are I and I am you” the prayerful poverty of this holy widow offered to the Lord the only response truly commensurate to the wondrous mystery such words express: the radical friendship of spousal devotion which wants to be given and to be possessed completely all the more when confronted by the mystery suffering, privation, hostility, and death.

Note from Dan: Anthony’s fantastic book on prayer, Hidden Mountain Secret Garden, can be found HERE in print, and HERE in Kindle format

Information about the book can also be found here on Facebook.

+

Art for this post on Saint Angela di Foligno: Angela de Foligno, unidentified author, XVIIth century print, PD-US author’s life plus 70 years or less, Wikimedia Commons.