Dear Father John, I really want to think of God as good but lately I have been struggling with all the suffering I see around me and in my own life. Where is God in all of this?

Suffering and sorrow challenge our faith in God. They push us out of our spiritual comfort zone as we find ourselves asking: If God is all-powerful and all good, why doesn’t he just fix everything, why does he let so many bad and painful things happen – why doesn’t he just get rid of all the world’s evil and injustice? This was Job’s dilemma in the Old Testament. It was even a challenge faced by Jesus himself in the Garden of Gethsemane, and the Blessed Virgin Mary had to grapple with it as she watched her only Son being humiliated, unjustly condemned, tortured, and crucified on Calvary. So you are in good company. Every human person, in fact, has to face this question at some point or another. But we never have to face it alone. Although at times God seems distant in the midst of suffering and sorrow, he is not. He is right by our side, carrying us and supporting us and enlightening us, if we let him. Two reflections, one doctrinal and one practical, may help you find him and lean on him as you navigate these treacherous waters.

God’s Answer to Evil

The Catechism – the systematic explanatory summary of God’s revelation in Christ – puts a spotlight on this question, and boldly gives us the doctrinal answer. Because this issue is so central to Christ’s message, and to our daily lives, I will quote the whole paragraph (#309 – the underlinings are mine):

If God the Father almighty, the Creator of the ordered and good world, cares for all his creatures, why does evil exist? To this question, as pressing as it is unavoidable and as painful as it is mysterious, no quick answer will suffice. Only Christian faith as a whole constitutes the answer to this question: the goodness of creation, the drama of sin and the patient love of God who comes to meet man by his covenants, the redemptive Incarnation of his Son, his gift of the Spirit, his gathering of the Church, the power of the sacraments and his call to a blessed life to which free creatures are invited to consent in advance, but from which, by a terrible mystery, they can also turn away in advance. There is not a single aspect of the Christian message that is not in part an answer to the question of evil.

You may have to read that paragraph more than once for it to sink in. Basically, God did not create evil and the suffering that evil causes, directly or indirectly. God created the world good, but he gave angels and humans free will. When the devil abused this freedom by rebelling against God, evil entered the universe. When the devil tempted Adam and Eve, and when they decided to follow him instead of God, that evil entered the human realm as well. Evil is not something positive, but negative. Just as cold is not something positive, but negative – it is the lack of heat. And darkness is not something positive, but negative – the lack of light. Just so, evil is the absence of some good that was part of God’s original design. When a free creature (an angel or a human) deviates from God’s plan, suffering is the logical result. And since we are all connected – we were created to be God’s family; the human race was created to be one human family, in which the actions of one person affect others, for good or ill – the sin of Adam had repercussions for all of us, just as the sin of an abusive dad or an over-possessive mom has repercussions for their children.

God Didn’t Create Robots

If God had created angels and humans without free will, he could have avoided all evil. But then you and I would be nothing more than robots. We would not be capable of love, which involves the free gift of self to another person. And if we were incapable of love, we would not be created in God’s image and likeness. And without that likeness, we would not be able to enter into heaven, the communion of life and love with God. So God took the risk.

If God had created angels and humans without free will, he could have avoided all evil. But then you and I would be nothing more than robots. We would not be capable of love, which involves the free gift of self to another person. And if we were incapable of love, we would not be created in God’s image and likeness. And without that likeness, we would not be able to enter into heaven, the communion of life and love with God. So God took the risk.

Of course, in his omnipotence and omniscience, he is able to repair the damage done by sin and rebellion against his plan. The story of salvation, from the Garden of Eden to the Garden of Gethsemane to the New Jerusalem at the end of history, is the story of that reparation, the “redemption” of fallen humanity. In the life of every person who repents and returns to God, God shows his merciful and transforming love by mysteriously bringing forth good out of evil. This is hard for us to understand. But we get a glimpse of it by contemplating how God was able to work the most marvelous miracle in history, Christ’s resurrection, in the wake of the most horrific sin in history, the deicide of Christ’s crucifixion. This is the warp and woof of Christian life: Good Fridays followed by Easter Sundays.

Keeping the Whole Story in Mind

If we didn’t know this plan of redemption, there would be no option but despair in the face of the immense suffering and injustice of the world. But we do know the plan. We know the last scene of the story; we know that in the end “He will wipe away every tear from their eyes; and there will no longer be any death; there will no longer be any mourning, or crying, or pain; the first things have passed away” (Revelation 21:4).

The core Christian virtue of hope is what keeps this truth on our radar screen, so that we never allow ourselves to be drowned by frustration, discouragement, or cynicism. This why Pope Benedict XVI calls suffering a “setting for learning hope” in his Encyclical Letter Spe Salvi (In Hope We Are Saved) (see #s 35-40 for a wild, shocking meditation on the meaning of suffering). This is also why he calls God’s Last Judgment a “setting for learning and practicing hope” (see #s 41-48). Our lives here on earth, in the flow of human history, are not the whole story. We are pilgrimages, and God has promised that if we trust and follow him, all the suffering and pain of this life will be transformed into glory: “And we know that God causes all things to work together for good to those who love God” (Romans 8:28).

In our next post on this topic (next Monday) we will talk about a practical approach to living in this reality.

+

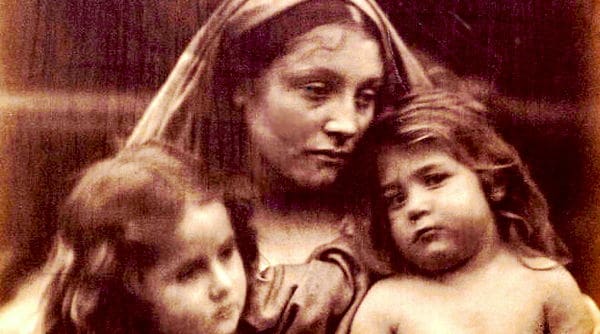

Art for this post on struggling with suffering: Modified detail of Long-suffering, Julia Margaret Cameron, 1865, PD-US author’s life plus 100 years or less, published prior to January 1, 1923, Wikimedia Commons.