A Reflection from “After Christendom” by Michael Warren Davis

Who is the man who desires life, who loves to behold good days? Keep your tongue from evil and your lips from speaking deceit. Depart from evil and do good; seek peace and pursue it. —Psalm 33:12–14

It is only with the heart that one can see rightly. —Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Before we go any further, I should probably concede that little I say here is especially original. I myself first came across these ideas in Charles Péguy, who wrote: It is the mystic who is practical, and the politically minded who are not. It is we who are practical, who do something, and it is they who are not, who do nothing. It is we who accumulate and they who squander. It is we who build, lay foundations, and they who demolish. It is we who nourish, and they who are parasites. It is we who make things and men, people and races. It is they who wreck ruin.

C.S. Lewis made the same point in his masterpiece Mere Christianity. In chapter 10 (“Hope”), he warns that,

If you read history you will find that the Christians who did most for the present world were just those who thought most of the next. The Apostles themselves, who set on foot the conversion of the Roman Empire, the great men who built up the Middle Ages, the English Evangelicals who abolished the Slave Trade, all left their mark on Earth, precisely because their minds were occupied with Heaven.

It is since Christians have largely ceased to think of the other world that they have become so ineffective in this. Aim at Heaven and you will get earth “thrown in”: aim at earth and you will get neither. So did Father Seraphim Rose:

Christ is the only exit from this world; all other exits—sexual rapture, political utopia, economic independence—are but blind alleys in which rot the corpses of the many who have tried them.

Pope Benedict XVI likewise made the point in 1997, in what I call his “mustard seed prophecy”:

Perhaps the time has come to say farewell to the idea of traditionally Catholic cultures. Maybe we are facing a new and different kind of epoch in the Church’s history, where Christianity will again be characterized more and more by the mustard seed, where it will exist in small, seemingly insignificant groups that nonetheless live an intensive struggle against evil and bring the good into the world, that let God in.

So did Father Alexander Schmemann throughout his career, but most powerfully in For the Life of the World:

What am I going to do? What are the church and each Christian to do in this world? What is our mission? To these questions there exist no answers in the form of practical “recipes.” It all depends on thousands of factors—and, to be sure, all faculties of our human intelligence and wisdom, organization and planning, are to be constantly used. Yet—and this is the one “point” we wanted to make in these pages—“it all depends” primarily on our being real witnesses to the joy and peace of the Holy Spirit, to that new life of which we are made partakers in the Church. . . . It is only when in the darkness of this world we discern that Christ has already “filled all things with himself,” and that these things, whatever they may be, are revealed and given to us full of meaning and beauty. A Christian is the one who, wherever he will, finds Christ and rejoices in him. And this joy transforms all these human plans and programs, decisions and actions, making all his mission the sacrament of the world’s return to him who is the life of the world.

Of course, there’s Rod Dreher’s “Benedict Option”:

If we want to survive, we have to return to the roots of our faith, both in thought and practice. We are going to have to learn habits of the heart forgotten by believers in the West. We are going to have to change our lives, and our approach to life, in radical ways. In short, we are going to have to be the church, without compromise, no matter what it costs…. If we are going to be for the world as Christ meant for us to be, we are going to have to spend more time away from the world, in deep prayer and substantial spiritual training, just as Jesus retreated to the desert to pray before ministering to the people. We cannot give the world what we do not have.

There’s Paul Kingsnorth’s “Wild Christianity”:

I feel like I am being firmly pointed, day after day, back toward the green desert that forms my Christian inheritance, toward that “ardent and active solitude.” Back to the song that is sung quietly through the land by its maker, the song that is in the stream running, in the mist wreathing the crags, the growling of the rooks, the thunder over the mountains. Back to the caves, to the skelligs, to the deserts green and brown, to stretch out my arms crossfigel and recite the great prayer of St. Patrick’s Breastplate: “The light of the sun, the radiance of the moon, the splendor of fire, the speed of lightning, the swiftness of wind, the depth of the sea . . .” I feel that in another time of crisis and confusion we need to go back to our roots, both literal and spiritual. To flee from the gaze of a civilized center that denies God and launches salvo after salvo daily against the human soul. To seek out a wild Christianity, which will see us praying for hours in the sea as the otters play around us. To understand—to remember—that the Earth and the world are not the same thing.

There’s Father Calvin Robinson and Matt Fradd on Pints with

Aquinas:

Robinson. I don’t think it’s even possible for conservatives to conserve Western civilization anymore. It’s up to Christians—if it is going to be conserved. I actually think it’s probably too late, and Western civilization has peaked and we’re on a downward trend now. Which is fine, because us Christians, we have hope in what’s to come….

Fradd. I think I’ve come to the opinion that Western civilization is dead. . . . Which is actually kind of freeing. Because you don’t have to keep holding up a structure that doesn’t exist. We can think of ourselves, as Pope Francis says, as medics in the field.

And we could give many more examples, from George MacDonald, G.K. Chesterton, Eberhard Arnold, Jacques Maritain, T. S. Eliot, Dorothy Day, Seraphim Rose, Alasdair MacIntyre . . . The list goes on and on. Many have urged Christians to make peace with the loss of worldly power. Many have urged us to embrace our traditional role as suffering servants. But somehow this thesis is still extremely controversial—or, at best, deeply, even willfully, misunderstood. Many great men and women are telling us to stop hiding in the pews and start making disciples of all nations. Yet somehow they’re dismissed as “retreatists,” “quietists,” even “defeatists.” Why? Because we’re afraid.

To purchase this book, please visit one of the links below.

_

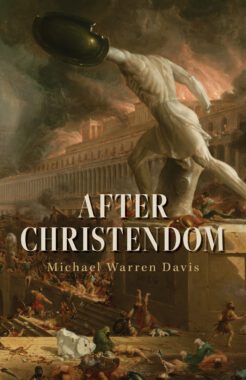

This article on ‘Abandon All Hope? Not So Fast.’ is adapted from the book After Christendom by Michael Warren Davis which is available from Sophia Institute Press.

Art for this post on a reflection from “After Christendom” by Michael Warren Davis; cover used with permission; Photo used in accordance with Fair Use practices.