Fr. Paul Mankowski, S.J., is not a common Catholic household name like Archbishop Fulton Sheen, Fr. Mike Schmitz, or Fr. James Martin, S.J. He would have been had he not been silenced by the superiors of his religious order, the Society of Jesus, the Jesuits. In 2003, the Jesuits banned him from writing and from speaking on anything other than his area of expertise—ancient Semitic languages. He lived forty-four years as a Jesuit and was forced to remain silent for many of those years. He was carefully kept away from impressionable young minds, as well as other old-school Jesuits, lest they pool forces and become, as liberal Jesuits refer to them, Shadow Formatores—men who are a bad influence on novitiates because they are “rigid traditionalists.” What was Fr. Mankowski’s crime? Faithful obedience to the Magisterium of Holy Mother Church. That, and a severe love of the Truth, and an inability to keep his mouth shut about it.

The obituaries that came out after his death were written by scholars, fellow priests, close friends, a famous cardinal, and even a prime minister. All of them do as good a job as possible in describing Fr. Paul, yet none of them do him justice in describing the whole man. A thorough reading of all the tributes might begin to give you an idea. What makes Fr. Paul Mankowski, S.J., so elusive and yet so striking is that he was a mixture of many things that do not go together. He was a mental giant but also a self-proclaimed jock. He was a serious scholar, but he was scathingly funny and extremely playful. He could and did eviscerate people with the written word as his weapon, but he was one of the kindest, gentlest, most compassionate people I’ve ever known. He was a Jesuit’s Jesuit, but only if you go by the standards of dead Jesuits. He was, for my money, a miracle of a person.

There is a glaring absence in the obituaries and tributes, though, and that is the story of what he suffered at the hands of his Jesuit brothers. There are cryptic references, and one writer went so far as to say this: “He was silenced by the Society, the ultimate tribute which those who cannot bear the truth bestow upon those who forcefully proclaim it.” Highly accurate, but there is no room in a short tribute article to go into detail. The persecution that Paul Mankowski suffered lasted many years and took on many forms. Someone would have to write a book to describe it fully. I decided that maybe it wasn’t a coincidence that Paul had befriended a writer, so I volunteered for the job.

I wanted to come up with a story that would serve well as an introduction, for those who needed one, to Paul Mankowski the man and would also give insight into the problems he had with his fellow Jesuits. There is a story that serves both purposes, and I will let Paul tell it himself. Way back in 2007, I had asked him (in an e-mail) why he always wore clerics. The following was his response:

“As a scholastic, I didn’t wear clerics. Partly this was because clerics confuse people who took them as a sign of priesthood. (“Well, like, what priest-things can you do and not do?”) But mostly it was because life is just a lot easier when you’re not wearing them. My mind on the subject was changed by one offhand comment and one not-so-offhand event, both of which occurred in my first year of priesthood (when I was studying at Weston, in Cambridge, MA). The offhand comment was by a layman and a Harvard grad student who knew the Jesuit community very well and remarked to me, “You know, if you guys did nothing different from what you do now, but started wearing clerics, it would stun Harvard. You’d have ninety men walking around Harvard Yard every day whose dress announced that they take Christ seriously.” I thought: damn. He’s right.

The event was a mandatory all-community morning on Jesuits with AIDS (there were a number of AIDS deaths in those years), in which the Vice Rector told a story about his lying on a beach in Provincetown two years previously with two men talking about AIDS, one of whom had since died and the other of whom was HIV-positive, etc. He, and the other community leadership, went on to declare (in effect, not in so many words) that the Society of Jesus rejected Church teaching on homosexuality. It was a kind of institutional apostasy happening before my eyes. I went for a long, long walk afterwards, during which I promised myself that I would never appear at another Jesuit function (be it even breakfast in my own house) not wearing clerics. It was a sign of protest, a kind of full-body black armband. Unless I’m deluding myself, it’s a promise I’ve never broken, either.

Returning to the more general level, and repeating myself, things are more comfortable for a priest who’s not wearing clerics, but there’s nothing especially noble about the comforts enjoyed. E.g., black is hot and hard to keep clean and the collar is tight. Civvies are not only more comfortable, but they give you anonymity. Civvies let a priest go to the kind of bars and restaurants that a man in clerics would be shy of entering. . . . They let the priest buy the kind of reading material that would raise eyebrows otherwise. They free the priest from the obligation to edify—or at least not be disedifying. In civvies the priest can flip off people who cut him off in traffic and yell nasty things at panhandlers and argue with salespeople and waiters and airline personnel without regard to an institutional reputation to uphold. And, of course, civvies give the priest the prerogative to reveal his priesthood to those he wants and withhold from those he wants. Though it’s a temptation I resist, the biggest temptation for me to crawl into civvies comes just before a long flight, so I don’t have to get into discussions about my fellow passengers’ problems with divorce, their anger at (or loud, loud, LOUD enthusiasm for) the Church, their fight with Father Murphy, their mystical experiences on the beach, their certainty that the true church is the church of Mormon of the disciples of Christ, etc., etc. Sometimes you just want to be Mister Average Passenger.

However, turning yourself into Mister Average Passenger —for a priest—is like Frodo Baggins putting on the Ring in order to disappear. It’s a sneaky way out that makes you a tiny bit more cowardly every time you take it.

Regarding the freedom to misbehave in civvies, one of the priests I admire was known to say: if you feel the need to remove your clerics to go someplace, you shouldn’t be going there. Regarding the witness value generally, the bottom line is that priesthood is not a job that you take up at 8:30 and put down at 4, but a lifetime vocation. As I say, except for showering , bass fishing (and yes, sleeping), there’s almost nothing I do that I can’t do in clerics if I really want to.”

+

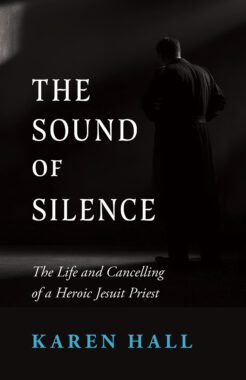

This article on ‘Cancel Culture – What a Faithful Jesuit Priest Can Teach Us’ is adapted from the book

The Sound of Silence: The Life and Canceling of a Heroic Jesuit Priest by Karen Hall which is available from Sophia Institute Press.

Art for this post on a reflection from “The Sound of Silence: The Life and Canceling of a Heroic Jesuit Priest” by Karen Hall: cover used with permission; Photo by Gregorio Lazzarini.