Silence is a hallmark of prayer in many religious traditions. It carries with it a certain awe, as if maintaining extended periods of silence were supernatural in itself, but in reality, it is part of the human life’s natural commute from solitude to encounter. Silence creates a separation that allows one to move away from an external focus on human activity and enter more fully into an interior dialogue.

The experience of silence is that the human spirit begins naturally to rise toward God or go deeper inward, where God dwells within us. Especially when we enter into peaceful, beautiful, holy places that feel safe, our hearts can settle and naturally rise in openness to the divine and can swell with gratitude for our lives.

This can be harder when the environment is chaotic, disorganized, ugly, or marred by a history of violence. Likewise, when events trigger something in us and our nervous systems move into a state of hyperarousal—fight or flight—because of a real or perceived aggressor, it is impossible to settle into silence. In that case, we hear only the pounding of our own hearts until we can recover a sense of safety and are able to ground ourselves.

At times, we avoid silence because, in this interior movement, it can become evident where our attachments lie. When the external occupations cease, thoughts and feelings begin to rise within. These can point to places of pain in our hearts, and the pain can begin to resurface. The thoughts that come up might repeat painful phrases or try to work through difficult and confusing interactions. The less self-reflection we make time for, the more difficult it is for us to track what is happening in our minds and bodies.

The lament of St. Augustine captures this: “Late have I loved Thee, O Beauty so ancient and so new, late have I loved Thee! And behold, Thou wert within and I was without. I was looking for Thee out there, and I threw myself, deformed as I was, upon those well-formed things which Thou hast made. Thou wert with me, yet I was not with Thee. These things held me far from Thee.” St. Augustine found himself unable to enter inside himself in silence to meet God within him and continued pushing to the exterior to find God in places that were within his control.

Silence can make us feel out of control, as we may face our uncontrollable restlessness or our guilty consciences when we enter into silence. Entering into silence can feel like a stripping away of comforts in a way that confronts us with reality. We face our existential contingency—we cannot sustain ourselves in being by our own power—and the otherness of all things. At the same time, with faith, this can help us to realize that we are willed into being by another, meaning that our lives are a gift, and all other things that exist also have the quality of a gift. We do not have to control them or create them but only receive them from the fullness of God. Pope Benedict XVI described this experience of silence when he spoke at the Carthusian Charterhouse near Rome: “By withdrawing into silence and solitude, human beings, so to speak, ‘expose’ themselves to reality in their nakedness, to that apparent ‘void,’. . . in order to experience instead Fullness, the presence of God, of the most real Reality that exists and that lies beyond the tangible dimension.”

Dr. Conrad Baars, a Catholic psychologist, also describes the way that silence can help to heal the unaffirmed and support everyone in living “the affirming life.” The affirming life, in the language of Dr. Baars, is the capacity to respond emotionally to the goodness of reality and to engage the mystery of reality with awe and wonder. For us to live in this way, he counsels restricting the activity of the mind, so often filled with “an abundance of thoughts, judgments, opinions, comparisons, if not prejudgments and a know-it-all-attitude.”19 The overstimulated mind of modern man inhibits the potential for awe and wonder and limits our capacity to discover a deeper meaning in the things we have seen many times before:

His overdeveloped, overstimulated “mind” prevents his “heart” from being present with the awe and wonder of a child who sees a dandelion for the first time; from letting the unknown become part of him, to let the mystery of the unknown be and not demand it to be like the already known. His “mind” prevents his “heart” from being moved with love and joy and tenderness, from being authentically present to the other for the sake of the other.

At the same time, Dr. Baars recognizes that such openness of heart is not easy. In fact, such openness is very vulnerable. If we open our hearts to others, we can easily be hurt. We have learned to close our hearts because of pain from wounds of our past. For this reason, it can be a benefit to practice silence in nature, where our openness of heart is safer:

The unaffirmed person, therefore, must dare to restrict the activity of his “mind” so his “heart” can be more open and sensitive. It takes courage to be open with the “heart,” for one is more vulnerable when one relinquishes the protective workings of the “mind.” For this reason the unaffirmed person must first apply these principles only to the world of animals, plants, and minerals—to what we usually call nature. In that world he cannot be hurt as he has been hurt by the human beings who failed to be present to him. For the time being, while engaged in “natural or earthly contemplation” he must try not to “bother” with people, or at least to do so as infrequently as possible.

Discovering the dynamics of the gift of creation is one way to encounter silence. Another is to realize that God wants us to know that He is a Father who loves us, and He gives us permission to view our restlessness in silence like the fidgeting of a little child. Cardinal Sarah describes the childlikeness that can develop in the asceticism of silence: “The asceticism of silence allows a person to enter into the mystery of God by becoming little, like a child. . . . Silence strips man and makes him like a child: pure but frail, innocent, and without provisions.” Our flurry of words and our frenetic activity are defenses that we use to protect ourselves, to shield ourselves from the nakedness that we can feel in silence, but if we can allow ourselves to be held lovingly and patiently by our Heavenly Father, we can learn to settle slowly into the silence.

The good news is that these experiences of our restlessness can alert us to our need for God. Like the thorn in the flesh that St. Paul describes (2 Cor. 12:7–10), our inner reactions to silence can alert us to a greater need for God’s grace. And God always desires to provide for us in our need. Behind all our psychological defenses there is something to defend—a vulnerable part of us that is in need of special care. The defenses that are exposed by entering into silence can reveal parts of us that are feeling particularly vulnerable. We can come to discover inner wounds that can become the occasions for grace, as God promised St. Paul: “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Cor. 12:9).

Bringing all of this together, we can say confidently that silence is important for our spiritual life, for self-knowledge, and for our inner healing. It’s no wonder Jesus entered repeatedly into silence, providing an encouraging example for us. And it’s no wonder the liturgy also provides spaces of silence for us to enter more deeply into the Sacred Mysteries made present in the words and gestures of the rite.

As mentioned earlier, silence can also have a negative meaning. While some people’s defenses include a flurry of words or frenetic activity, others’ defenses include shutting down, clamming up, and freezing. In this case, silence can become a kind of hiding place, as Adam found in the garden when he felt shame. Silence can be more oriented to keeping others out than to keeping something precious safe. This leads to the passive-aggressive behavior called the silent treatment, when one person intentionally shuts down another. Here again, it would be unhelpful simply to condemn this behavior in ourselves and more valuable to seek the underlying cause. What vulnerable part of us are we defending by wielding silence in this way?

In the world of social media, this has become known as “ghosting,” indicating that a person acts toward another as if he or she has disappeared, by not answering e-mails or messages or any other kind of electronic communication. These are negative experiences of silence, when silence is used as a psychological weapon or as a psychological defense. This is very different from what Jesus was exhorting us to incorporate into our lives: “When you pray, go into your room and shut the door and pray to your Father who is in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you” (Matt. 6:6). Rather than encouraging ghosting, Jesus is inviting us in these words into a safe place of hidden intimacy with Him, where we can receive the love He wants to bring to the littlest and most vulnerable parts of us.

The silence that is prescribed in the liturgy should be viewed in this positive way as creating places of hiddenness that make us secure enough to be vulnerable, like little children, and open to the loving embrace that our Father extends to us. We are stepping away from a flurry of words and activity, often laced with the harshness of this fallen world, in order to hear and savor the words of love that our Father whispers to us as His beloved children. In this way, the liturgy, with its ritual gestures and prescribed silences, provides a kind of veil beneath which we are safe to confront the reality of ourselves in all our strengths and weaknesses and the reality of God in all His love. Romano Guardini describes this beautifully:

The liturgy is wonderfully reserved. It scarcely expresses, even, certain aspects of spiritual surrender and submission, or else it veils them in such rich imagery that the soul still feels that it is hidden and secure. The prayer of the Church does not probe and lay bare the heart’s secrets; it is as restrained in thought as in imagery; it does, it is true, awaken very profound and very tender emotions and impulses, but it leaves them hidden. There are certain feelings of surrender, certain aspects of interior candor that cannot be publicly proclaimed, at any rate in their entirety, without danger to spiritual modesty. The liturgy has perfected a masterly instrument that has made it possible for us to express our inner life in all its fullness and depth, without divulging our secrets—secretum meum mihi. We can pour out our hearts and still feel that nothing has been dragged to light that should remain hidden.

+

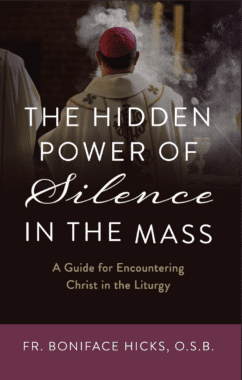

This article on Nurturing a Culture of Silence in the Modern World is adapted from the book The Hidden Power of Silence in the Mass by Mary Jane Zuzolo which is available from Sophia Institute Press.

Art for this post on a reflection from “The Hidden Power of Silence in the Mass” by Fr. Boniface Hicks: cover used with permission; Photo by Isabella Fischer on Unsplash