Pope Benedict XVI saw the need for an education in silence in our time: “Ours is not an age which fosters recollection; at times one has the impression that people are afraid of detaching themselves, even for a moment, from the mass media. For this reason, it is necessary nowadays that the People of God be educated in the value of silence.” How can we bring about this education in the value of silence?

Silence is an overloaded term that can be studied from many perspectives. We can speak about sound waves, and we can measure these sound waves to rate various noise levels using the metric of decibels. In this way, we can identify the “most silent” place in the world. We could call this lack of sound waves “physical silence” because it is simply a matter of physics. Physical silence is impersonal, so it does not capture the dimensions of silence that we are most interested in when speaking about the spiritual life. When speaking about silence as a human phenomenon, we are interested primarily in interior silence. In contrast to the decibels of physical silence, a “personal silence” or “interpersonal silence” is always in reference to words, in the sense of communication. Twitter, for example, does not produce decibels, but it does interrupt personal silence.

Physical silence and personal silence can coexist, of course, but they are clearly distinct. For example, a man could be standing in the most silent place in the world and still lack personal silence, as he experiences a flood of words in his mind. Likewise, a deaf person who always experiences the world as being physically silent could be overwhelmed by the number of words he is receiving from a room full of people speaking in sign language. Contrariwise, a person in a jungle filled with physical sounds could experience an interior, personal silence that is free from words. Or, again, a person hearing the high decibels of a waterfall could enjoy an interior silence in the peace of his heart as he gazes on the beauty of order in nature.

The philosopher Bernard Dauenhauer describes silence as a cut in our inner stream of experience:

Dauenhauer notes that discourse always finds a pre-predica-tive stream of experience which is essentially endless and never fully determinate. He terms this feature the “and so forth” of experience. . . . The shift from the “and so forth” to discourse involves a “cutting” into that otherwise endless progression. The “cut” is not, in the first instance, word, but silence.

There is undoubtedly a relationship between physical silence and personal silence, as noted by Cardinal Robert Sarah: “Just as interior asceticism cannot be obtained without concrete mortifications, it is absurd to speak about interior silence without exterior silence.” Exterior silence creates an experience that can lead to interior silence by first leading to interior awareness. As Fr. Réginald Garrigou-Lagrange described it: “From the moment he ceases to converse with his fellow men, man converses interiorly with himself about what preoccupies him most.”11 This internal stream of words in man’s conversation with himself can be drawn steadily into conversation with God: “As soon as a man seriously seeks truth and goodness, this intimate conversation with himself tends to become conversation with God.” Furthermore, because God is beyond all finite words — indeed, it could be said that the language of God is silence — this interior conversation tends more and more to interior silence.

In reflecting on personal silence, we could further differentiate several kinds of silence. There is a basic difference between the types of positive silence, in which beauty can grow, and the types of negative silence that can be used as a defense (the silent treatment). Within the types of positive silence, we identify five:

- ascetical silence, a preparation, making room to receive

- mystical silence, an encounter that happens through listening

- sacrificial silence, the self-gift that forms the response to the encounter

- contemplative silence, adoration and communion

- eternal silence, a timeless savoring of the communion

These silences follow a basic flow that moves from making space (ascetical) to abiding in transforming union (eternal). This fivefold movement is creative, serving as the pattern in which life came forth on this earth and the pattern through which divine life comes forth in the soul. It is the pattern of Creation in Genesis, the pattern of the Incarnation in Mary, the pattern of silences in the Mass, and the pattern of transformation in our souls.

This pattern of movements in silence appears in the first account of Creation. First, there is a silence that precedes the Word and, in a sense, prepares for it: “The earth was without form and void” (Gen. 1:2). We might say that this void is listening so as to hear the Word, and then there is the moment the silence encounters the Word: “God said, ‘Let there be light.’ ” The silence yields to the Word (gives itself in response, so to speak) so that a new reality comes into being: “And there was light” (Gen. 1:3). This new reality is now a mystery that can be divinely pondered in the silence—“And God saw everything that he had made”—and savored: “and behold, it was very good” (Gen. 1:31). This is the pattern of Creation. In this original pattern, the silence does not have free will, so the listening and yielding happen automatically.

In the Redemption, God cooperates with Mary’s free will and makes a new creation in the silence of her womb. We can trace the same movements of silence as in the original Creation. First, Mary makes space: created without sin, she presents no hindrance to the Word. Through listening, she encounters the Word first through the angel who announced His coming. Then, in response, she offers herself in silence to receive the Word. This gives birth to a mystery beyond words in contemplative silence. Finally, Mary is left in silence to savor tenderly the mystery that had been conceived in silence. These are the movements of silence: preparing for the Word, encountering the Word, offering oneself in response to the Word, birthing a mystery that transcends words, and tenderly savoring the mystery. These are the movements not only of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the woman of silence, but also of the Church, especially in her liturgy, and these movements steadily form the heart of every believer who is willing to enter into the Church’s liturgy.

In these movements, we can see an alternation of action and reception. The active preparation, creation of a space, and waiting are followed by a silence of encounter, which is reception. Mary does not create the encounter, only the space, but then the encounter happens to her as she listens in silence. Her response is an action, a self-offering in silence. This is followed by another silence that happens to her, a conception, which moves her to adoration. Her final action is savoring, to remain with the Word, now conceived within her, in silence. The difference between encounter and conception lies in the response—a movement to the action of self-offering, in the case of encounter, or a kind of completion that moves to savoring the gift, in the case of conception (which, in the liturgy, is experienced as adoration and communion).

The Church’s liturgy in the Roman Rite uses intentional periods of physical silence to capture and foster these various movements of personal silence. These are intended to provide a “cutting” in the interior stream of experience so as to foster a movement in the heart of the believer in relationship to the Word. The better we understand the rationale behind these ritual gestures of liturgical silence, the better we will be able to correspond with them and so be transformed by the Word in our liturgical worship.

The Church’s liturgy engages silence in each of the ways just listed, and this will provide a structure for our reflections in this book. Prior to Mass and in the Introductory Rites, the participant is encouraged to foster an ascetical silence to prepare space for encountering the Word (chapter 2). Then, in a mystical silence, the participant encounters the voice of God in the Liturgy of the Word (chapter 3). This invites a response of self-offering in a sacrificial silence (chapter 4). Following the self-offering, the Word becomes incarnate in the participant and really present on the altar and is adored and received in contemplative silence (chapter 5). Finally, the participant remains in a timeless or eternal silence to savor the divine presence (chapter 6).

Before entering into the specific dimensions of praying through the movements of silence in the liturgy, we will look more generally, in chapter 1, at the dynamics of silence in personal prayer and the Church’s prescriptions for silence in the liturgy. We will conclude each chapter with a look at the example of Mary as the supreme model of silence for us. We will also learn from a great saint of silence and a lover of liturgy, St. Benedict. Additionally, I will provide concrete practices to foster the movement of silence discussed in the chapter.

To conclude our introduction, let us consider a summary invitation by Pope Benedict XVI, who captures each of the dimensions we highlight—the purification, listening, offering, bringing to birth, and contemplation:

How can we open the world, and first of all ourselves, to the Word without entering into the silence of God from which his Word proceeds? For the purification of our words, hence, also for the purification of the words of the world, we need that silence which becomes contemplation, which introduces us into God’s silence and brings us to the point where the Word, the redeeming Word, is born.

+

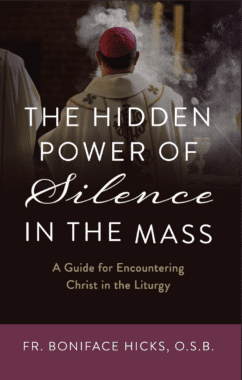

This article on Nurturing a Culture of Silence in the Modern World is adapted from the book The Hidden Power of Silence in the Mass by Fr. Boniface Hicks which is available from Sophia Institute Press.

Art for this post on a reflection from “The Hidden Power of Silence in the Mass” by Fr. Boniface Hicks: cover used with permission; Photo by Ümit Bulut on Unsplash