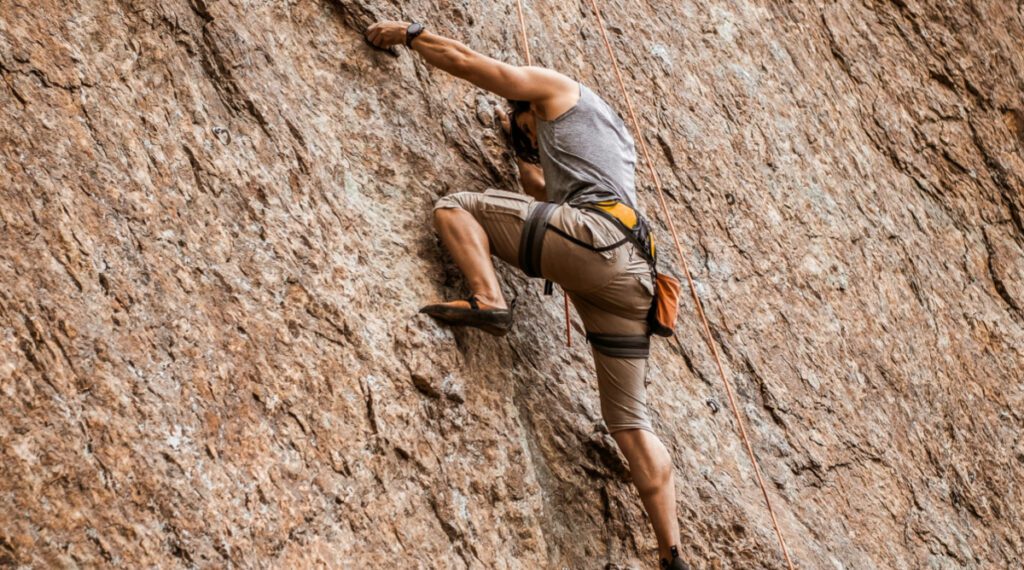

It is time to rouse ourselves and go out quietly into darkness, to begin a difficult and exciting journey, into the night.

The Ascent of Mount Carmel is the first part of what St. John of the Cross intended to be a single work. The second part comes to us as a separate volume, The Dark Night. The two are intended to be read together, beginning with The Ascent. St. John introduces us to the metaphor for which he is most well-known: the dark night. It is the opening line of his most famous poem:

On a dark night, fired by love’s urgent longing–oh happy chance!–

I went out without being seen, my house being all at rest.

There was a time in St. John’s life when he had to do this, literally: he escaped into the night, from the monastery where he was being held prisoner, by his own fellow Carmelites who opposed the reform of the order that he and St. Teresa of Avila promoted. For nine months, he patiently endured solitary confinement in a closet, combined with physical and verbal abuse, and denial of many basic needs. The result was not what his captors intended. His closeness to God grew deeper and more profound, to the point that monks sometimes reported a mysterious light emanating from his cell. It was St. John of the Cross at prayer. Eventually, he discerned, in prayer, that it was time for him to go. Finding his door unsecured one night, he went out, walked past sleeping monks, and climbed down from a second or third-story window, using strips torn from his old habit to make a rope.

This daring escape provided the image that he would use for another kind of captivity, from which we all must struggle to escape: attachment to the appetites.

The dark night is a metaphor for purification.

In The Ascent, we are guided through the first night, which he calls the night of the sense. This is the stage of spiritual growth in which we must learn to separate ourselves from our desire for created things. Here we have an insight that has completely escaped the post-modern, quasi-Christian mysticism found generally under the heading of “centering prayer:” If you want a deeper relationship with God, you must reform yourself. Stop tolerating sensuality in your life; turn away from sin; get yourself to Confession; pursue virtue. Instead of meditating on inner emptiness, meditate on the Ten Commandments. All the centering in the world will only lead you to a dead end, or worse unless you focus on the moral teachings of the Church.

Along with moral reform, we must identify attachments to things. Our loves are many and varied. A person can say, “I love my children,” “I love my fiancé,” “I love my country,” “I love Dvorak,” “I love the Chicago Cubs,” “I love potato chips,” and all these declarations of love make sense. St. John of the Cross describes all such attractions as “appetites.” AMC III.16.1. Having appetites is unavoidable. By themselves, they do not stop us from growing in holiness. The threat comes when our will and desire are oriented toward the satisfaction of appetites. St. John calls these “voluntary appetites,” the ones that command our volition. We must separate ourselves from movements of the will that serve appetites.

This is not done by trying to convince yourself that you don’t like these things, but you must stop making them the objects towards which you direct your will. They are just facts about you, like the fact that you are 5 foot 7 and have brown hair and need reading glasses, or whatever those characteristics are. You happen to prefer Dvorak to Bach, the Cubs to the White Sox, and potato chips to cheese puffs. These are what St. John calls “natural appetites,” and it is impossible to completely mortify them in this life. (AMC I.11.2.)

What you can do is not seek out these things, and not let the denial of these satisfactions sour your mood or poison your charity. It is not the things themselves that hinder your progress, but your attachment to them. So work on breaking the attachment. This is where you must direct your efforts, in the active night of the sense.

Attachments also occur in the spiritual life. We become attached to consolations, to our ideas about God, to devotions, to ministries and causes, and to other things. St. John tells us that these attachments also must go. Here we find one of the central themes in all of his writings: we all tend to follow God through things, through ideas, devotions, causes, hopes, and loyalties. These may be good and important, but they are not God. If you follow St. John of the Cross, you must be willing to strip away from your spiritual life all attachments to whatever is not God. This is the work of the active night of the spirit.

How is this possible? The Ascent of Mount Carmel teaches how. It is hard work.

The nights have both active and passive aspects, and St. John explains these in detail. With some oversimplification, we can consider the active aspect as involving primarily one’s own efforts, while in the passive aspect, God’s grace directly draws the soul into deeper union. This is an oversimplification, because the night itself is a grace, even under the active aspect. The soul’s desire to proceed at all is a product of grace. So again we must distinguish St. John’s teachings from every mistaken belief that asceticism itself produces holiness, or that one’s own disciplines bring about true spiritual growth.

The soul undergoing purification is always in a mode of cooperating with grace, whether engaging the will to remain faithful to disciplines or experiencing effects that seem to come from outside.

To benefit from the graces of the passive night, you must be willing to allow God access to your deepest self. The passive night of the sense produces a diminishment in the natural appetites. The attachments begin to be purged by God’s own action.

The Ascent of Mount Carmel focuses more on the active purifications of senses and spirit. Next, St. John of the Cross explains the passive purifications. This is the subject of The Dark Night. Throughout these works, we are meant to see that prayer is essential because the ultimate aim of the spiritual life is union with God—not extraordinary mystical experiences, not works of charity, not promotion of worthy causes, not the conversion of sinners. These all are good things, but none of them is the ultimate aim of the spiritual life. In fact, the desire for them can become an obstacle.

Perfect detachment from all that is not God is what we will have in fullness in Heaven. So we should start actively seeking it now, here in this life.

Alone in his prison cell, St. John of the Cross was deprived of everything one could desire. He was left only with God. He tells us that, when you love God as you should, as He desires you to love, then God is enough.

Photo by Omid Armin on Unsplash.