IT SEEMS TO me we are always struggling to be born. Some days, when I kiss the altar, I’m Mary adoring her slain Lord. Other days, I arrive as Judas in the night. Either way, He still insists on dying for me.

The altar is our Bethlehem, a cradle holding an infant already pressed into poem by a crown of thorns, a stone monument like a baptismal womb or a grave marker. Christ’s suffering is love, and the love makes the poem. This is how that tiny baby surpasses His humility and reveals His true divine nature, and why St. John alludes to the fulfillment of glory through humility. The Word seems, at first glance, to be that and nothing more, an insignificant man. A fact. A note in the historical ledger to either be believed or disbelieved. Sure enough, He is a human man, but so much more.

Poetry suffers so deeply that it achieves the greatest freedom of all, the purest form of language. Circling round, descended from Heaven to earth and back again, Christ is a poetic revolution who swept away all my petty concerns. Because of Him, I’m not a passing fact. Neither are you. We’re that and more.

Underneath all our words, our attempts to speak and be heard, to hear and understand, our infant babble and speechless silence—underneath those words is not a what but a who, and that who loves us very much. So much so that He pours the universal into the concrete, living and dying on this earth and continuing to live and die in the Eucharist. The transcendent squeezed into the particular. This is His work.

This means that you matter. The people who matter to you matter. Your concerns matter. The little patch of green garden below your front window with the pink peonies in spring, your parish church full of quirky, delightful people filling the pews, your wobbly, inattentive prayers at Mass, the work you do, the bonfire you built for the kids, the t-ball game you watched in the park. Your creativity is important, the love you give, those halting attempts to learn to play piano, your penchant for Saturday morning hikes, the steam from the cup of your morning coffee. You are the particular, a person unlike any other, and your life is meant to be a unique embodiment of the divine. This is your work.

This is what the Mass taught me. I matter. I am caught up in a great communion of saints, a member of a single Body of Christ, but I am still me and the body wouldn’t be the same without me, for better or worse. God names us. He loves us. He pours His beauty into us

Above all, this work is gathered up in the liturgy—a word that literally means a public work. Don’t forget this sacred language of the Mass, the somewhat foreign, odd, countercultural worship of the Church. It’s worth contending for. Some people think it’s ridiculous, the reverence, awe, watered silk chasubles and old lace, chant flowing like waves to the shore, gently, covered in clouds of fragrant incense from which wavering flames light the lamp of home, and then the Host, the bells, the poetic mystery. This Mass that, by the hand of God, unmakes and makes. I think it saved me. It is saving all of us. I think it’s everything.

+

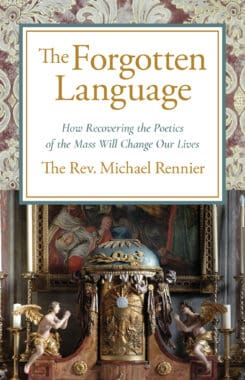

This article is adapted from a chapter in The Forgotten Language by Fr. Michael Rennier which is available from Sophia Institute Press.

Art for this post: Cover and featured image used with permission.