We give glory to you, Lord, who raised up your cross to

span the jaws of death like a bridge by which souls might

pass from the region of the dead to the land of the living.

— St. Ephrem

Not all battles in life’s larger conflict are equally important. Prudence dictates that we choose, and choose carefully, the hill we wish to die on — if we have a choice in the matter at all. But sometimes that choice is made for us, as in this battle for eternal life. Consequently, when a group of warriors takes a strategically significant point — a hill, a bridge, or a city — they are told to hold it at all costs as an essential objective for victory.

One such hill in the Easter Mystery is Calvary, the steep incline outside Jerusalem’s walls that may have taken its name from the bald outcrop of rock at its pinnacle. Calvary’s high ground rises to strategic importance during the Triduum, for it represents not only a tactical necessity in the war against Satan but also serves as the capstone in our paschal bridge to the Heavenly City. It must be taken, held, and fought for — even to the death. It is a hill to die on.

Like most battles, Calvary’s hill is charred, ugly, and deadly, a fact indicated by its original Hebrew name, Golgotha, “place of the skull” (Matt. 27:33; Mark 15:22; Luke 23:33; John 19:17). So foul a place, Calvary almost appears a place not worth fighting for. The long-suffering, just man, Job, prefigures Christ our Captain in this battle to hell and back via earth’s awful hill. “As Job sat on a dunghill of worms,” writes the fourth century’s St. Zeno of Verona, “so all the evil of the world is really a dunghill which became the Lord’s dwelling place, while men that abound in every sort of crime and base desire are really worms.” Such a harsh appraisal of human existence, of course, must be put in the greater context of Christ’s ultimate victory over mankind’s “crime and base desire” on Calvary.

The Good Friday liturgy provides such a context as it remembers (and makes present: anamnesis!) the pitched battle of Christ and our own “campaign of Christian service,” as Ash Wednesday called it. “On this day, when ‘Christ our passover was sacrificed,’ the Church meditates on the passion of her Lord and Spouse, adores the cross, commemorates her origin from the side of Christ asleep on the cross, and intercedes for the salvation of the whole world.” Our present journey into the Easter Mystery thus pauses — but does not rest — to meditate on three vital moments in the Good Friday conflict: the Passion and Cross endured by Christ, the Church’s new life emerging from Christ’s opened side, and the act of priestly mediation expressed in the Solemn Intercessions.

Passion and Cross

As we enter Good Friday’s celebration, it is important to keep in mind that the Good Friday liturgy is not a Mass. This fact itself should seem odd to us, since on every other day of the year the Church remembers Christ’s priestly sacrifice precisely by celebrating the Mass. On this day, though, the Bride of Christ recalls her Spouse’s saving work in other sacramental ways. Attentive ears will hear harsh yet life-giving truths in the liturgy’s opening prayer. After priest and deacon prostrate themselves for a period of silent prayer, they return to their chairs and the priest prays: “Remember your mercies, O Lord, and with your eternal protection sanctify your servants, for whom Christ your Son, by the shedding of his Blood, established the Paschal Mystery. Who lives and reigns for ever and ever. Amen.” Just as the Father has not forgotten His mercy, we march onward over the paschal bridge, reminded through the reading of His word that Christ’s work on Calvary is necessary in the war against death and sin.

The readings for the Good Friday liturgy paint a vivid picture of Christ’s Cross and death. Turning first to the Old Testament, we hear Isaiah describing the gory details of the death of the suffering servant. But first he calls us to open our eyes and witness the outcome of this ordeal: “See, my servant shall prosper, he shall be raised on high and greatly exalted” (Isa. 52:13, emphasis added). Here and elsewhere during this liturgy, the Church calls us to see for ourselves, to behold, Ecce! In the Gospel, we hear Pilate say, “Behold, the man!” (John 19:5). During the adoration of the cross, the priest draws our attention by proclaiming, “Behold, the wood of the cross!” And before administering Holy Communion with the Eucharist held in reserve but not confected on this day, the priest exclaims, “Behold the Lamb of God.” Christ upon the Cross is a spectacle to behold and meditate upon throughout the year, but above all on this day.

But as Isaiah continues his prophecy, he reminds us that Christ’s actions are focused on our own predicament:

Yet it was our infirmities that he bore, our sufferings that he endured, while we thought of him as stricken, as one smitten by God and afflicted. But he was pierced for our offenses, crushed for our sins; upon him was the chastisement that makes us whole, by his stripes we were healed. . . .

Though he was harshly treated, he submitted and opened not his mouth; like a lamb led to the slaughter or a sheep before the shearers, he was silent and opened not his mouth. Oppressed and condemned, he was taken away, and who would have thought any more of his destiny? When he was cut off from the land of the living, and smitten for the sin of his people, a grave was assigned him among the wicked and a burial place with evildoers, though he had done no wrong nor spoken any falsehood. But the Lord was pleased to crush him in infirmity. (see Isa. 53:4–5, 7–10)

The Passion according to the Gospel of John for Good Friday (Palm Sunday uses accounts from Matthew, Mark, and Luke over its three-year cycle) completes and fulfills what was foreshadowed by Isaiah. The suffering servant of Isaiah is none other than Jesus. What was once only a shadow now suffers and dies in the flesh.

+

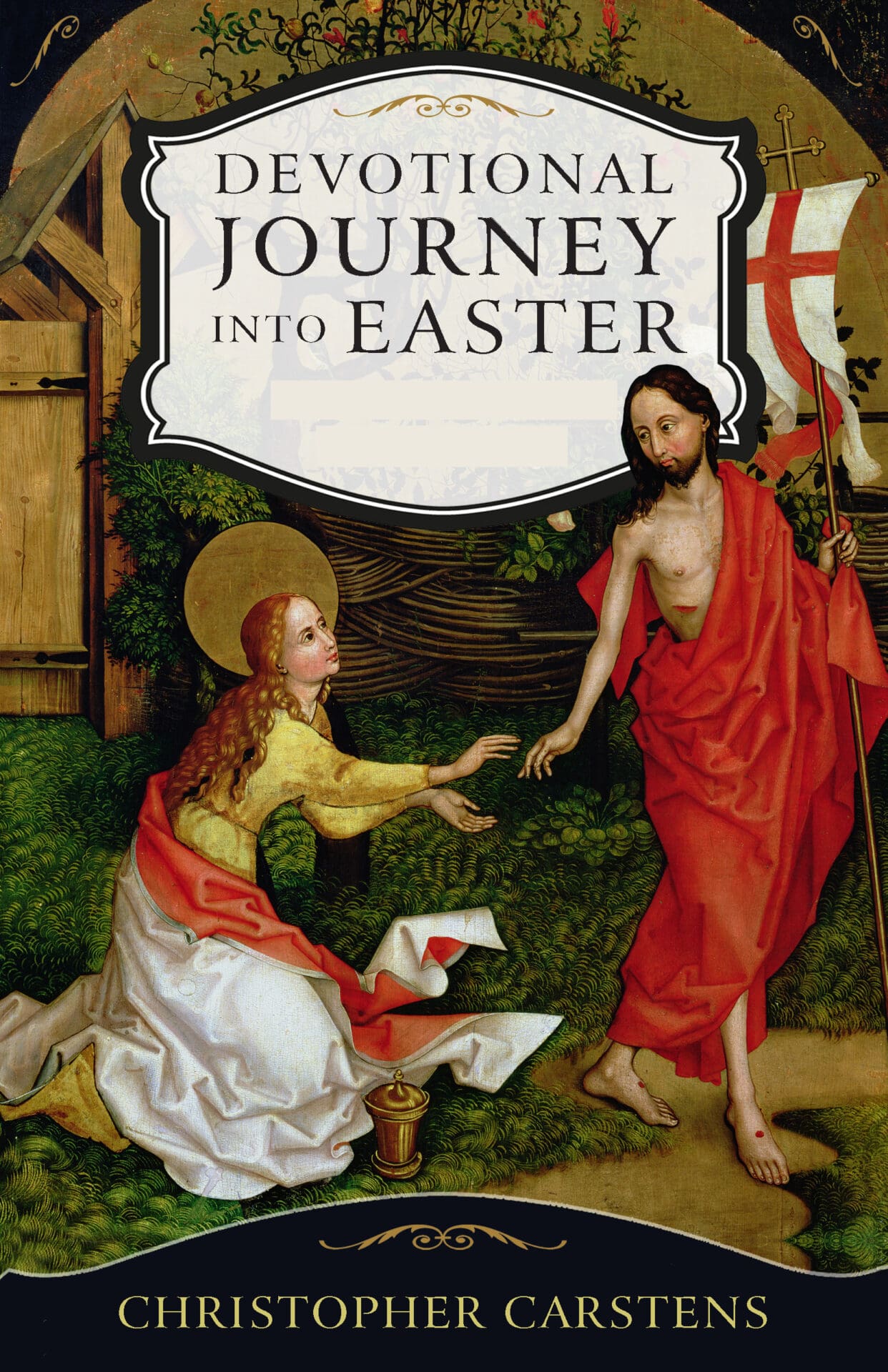

This article is adapted from a chapter in A Devotional Journey into the Easter Mystery by Christopher Carstens which is available from Sophia Institute Press.

Art for this post on Lent: Cover and featured image used with permission.