He is the mediator — the bridge, if you

will — between heaven and earth.

— Pope St. Paul VI

An essential element of any journey, devotional or otherwise, is the destination. If I don’t know where I’m headed, I can’t expect to map an enjoyable and efficient course. The Israelites of the Old Testament wandered for forty years in the desert, even though they knew their destination. But had they lacked even that knowledge, their forty years may have become four hundred. Our modern travels — summer vacations to new places, business trips out of town, or even the quick jaunt to the local grocery store — also require clarity of purpose. Getting from point A to point B is impossible if you don’t even know what point B is — or where it’s located.

The same is true of our spiritual journey though Lent. What is its purpose? Where is it leading us? What is our destination? If we know on Ash Wednesday where we are headed and what is to become of us at Easter’s grand conclusion, only then can we begin our trek with confidence — and in the sure hope of the resurrection.

So where are we journeying in Lent this year and, more broadly, in life now and forever?

The Church, who is both Mother and Teacher, goes to great pains to tell us about our destination throughout the Lenten season. On Ash Wednesday, for example, she reminds us of our goal as her priests bless the ashes:

O God, who are moved by acts of humility and respond with forgiveness to works of penance, lend your merciful ear to our prayers and in your kindness pour out the grace of your + blessing on your servants who are marked with these ashes, that, as they follow the Lenten observances, they may be worthy to come with minds made pure to celebrate the Paschal Mystery of your Son.

Further, on the First Sunday of Lent, we hear the following during the Preface at Mass (that is, the text immediately preceding the Sanctus or “Holy, Holy, Holy”):

By abstaining forty long days from earthly food, he consecrated through his fast the pattern of our Lenten observance and, by overturning all the snares of the ancient serpent, taught us to cast out the leaven of malice, so that, celebrating worthily the Paschal Mystery, we might pass over at last to the eternal paschal feast.

Are you beginning to hear a common theme, that is, a single destination — the Paschal Mystery? If so, you will find a further X marking the spot when you arrive at Palm Sunday, the doorstep of Holy Week. Prior to blessing the Palms for the procession into the Church, the priest introduces the celebration in these words:

Dear brothers and sisters, since the beginning of Lent until now we have prepared our hearts by penance and charitable works. Today we gather together to herald with the whole Church the beginning of the celebration of our Lord’s Paschal Mystery, that is to say, of his Passion and Resurrection.

If you identified the Paschal Mystery as Lent’s destination, your Lenten journey into the Easter Mystery is off to a great start. But let’s consider what this Paschal Mystery is, and why it’s the goal

of Lent and of life.

The Church is adamant that all of her members come to an intimate knowledge of — and an actual participation in — the Paschal Mystery. After the rites of Holy Week and the Easter Vigil were restored by Pope Pius XII in 1955, there appeared much enthusiasm for the revised rites — at least initially. Since that time, in some places, this eagerness to celebrate the Easter liturgies has waned. “Without any doubt,” says the Church’s instruction on the preparation and celebration of these feasts, “one of the principal reasons for this state of affairs is the inadequate formation given to the clergy and the faithful regarding the paschal mystery as the center of the liturgical year and of Christian life.”

The antidote to this inadequate formation, of course, is a greater familiarity with the Paschal Mystery, which is the destination of our earthly devotional journey. For this reason, “catechesis on the paschal mystery and the sacraments should be given a special place in the Sunday homilies” during Lent. But what’s good for the flock is also good for the shepherd, the Church recognizes, and so, before paschal preaching is possible, priests in training “should be given a thorough and comprehensive liturgical formation” so that they “might live fully Christ’s paschal mystery, and thus be able to teach those who will be committed to their care.” It can’t be stressed enough how important this formation is for both priests and laity. Jesus’ Paschal Mystery stands at the heart of His saving work and the center of the Easter Mystery. Lack of clarity on this central truth can result only in a wilderness wandering for the forty days of Lent. So, what is the Paschal Mystery?

The Paschal Mystery is “Christ’s work of redemption accomplished principally by his Passion, death, Resurrection, and glorious Ascension,” by which Jesus passed from the fallen world of sin to the heavenly world of the Father (see CCC 1067). These four distinct elements — suffering, death, Resurrection, and Ascension — are the substantial reality standing beneath each of Easter’s sacramental signs and symbols. They are called “paschal” because they form, as it were, a bridge by which Jesus and those who belong to Him cross over — that is, pass over — to a new heaven and a new earth (see Rev. 21:1).

But let’s take another step back and ask why Jesus needed to pass over from one side to another in the first place. Why did the chasm separating heaven and earth open? The answer to both questions is found “in the beginning,” or at least nearer to it than we are now.

All created beings — earth, angels, man — find their source in the heart of the Trinity. When reading the first lines of the creation account, for example, we encounter these three Divine Persons: “In the beginning, when God created the heavens and the earth — and the earth was without form or shape, with darkness over the abyss and a mighty wind sweeping over the waters — Then God said: Let there be light, and there was light” (Gen. 1:1–3). God, who is Father, creates by His Word — “God said” — and is accompanied by the Spirit, the “mighty wind.”

Creation, then, was from the start a reflection of the Trinity, is a well-ordered family of loving Persons: God the Father utters His Son, the Word of creation, with the breath of the Holy Spirit. Pope Benedict XVI observes that “Creation is born of the Logos [that is, the Word] and indelibly bears the mark of the creative Reason which orders and directs it; with joy-filled certainty the psalms sing: ‘By the word of the Lord the heavens were made, and all their host by the breath of his mouth’ (Ps. 33:6); and again, ‘he spoke, and it came to be; he commanded, and it stood forth’ (Ps. 33:9).” Cosmos, which in Greek means order and arrangement, is the root of the word cosmetics. Therefore, the cosmos was, from the start, cosmetic: a beautiful, well-ordered, living reflection of God.

But cosmos soon turned to chaos: ugliness, disorder, and death. Our state of original justice, giving to God what is due, was replace by original sin. As a concept, original sin is no easy truth for the intellect. In reality, though, original sin is as obvious as the sky is blue. English author G. K. Chesterton went so far as to remark that original sin “is the only part of Christian theology which can really be proved.” If you have any doubts, listen to a few minutes of any news broadcast — or just look around. But the universality of original sin aside, the nature of the Fall is difficult for man to understand. After all, why was eating an apple so wrong? And if Adam and Eve were already “like God” — they were made in His “image and likeness” (Gen. 1:26) — then why was falling for the serpent’s temptation of being “like gods” (Gen. 3:5) so egregious? What’s more, when God gave man a free will, wasn’t the Lord just setting His creation up for the Fall? These are essential questions, for they have a direct bearing on the Incarnation of Jesus, and His eventual Paschal Mystery. To put it another way, the “Bad News” of the first Adam either enlightens or darkens the “Good News” of the second Adam, Jesus.

Original sin is more than a matter of eating forbidden fruit — although that’s an important detail to know. It’s also more than our first parents merely wanting to be “like gods.” Saints, after all, are called “saints” because they are like God. In fact, Lent, Triduum, and the Easter season work to make us more like God than our finite, myopic vision could ever understand: “Through the Spirit,” says St. Basil the Great (d. 379), “we acquire a likeness to God; indeed, we attain what is beyond our most sublime aspirations — we become God.” Yet the forbidden fruit and the desire to be like gods back in the final days of Eden points to one unassailable truth of the Faith: our first parents’ sin consisted in reaching for their eternal destiny — being like God — but “without God, before God, and not in accordance with God.”

In other words, God had a plan from the beginning to lead His created order back to Himself in an unimaginable way (what the tradition calls the “economy of salvation”). The Father’s “two creating hands,” the Son and the Spirit, would guide us to an even greater intimacy and “God-likeness” than “in the beginning.” Our Fall — Adam’s, Eve’s, and ours today — results from our choice to get there our way, according to our own plan. But when this happens (as our experience confirms time and again), we jump the tracks, follow blind alleys, and find dead ends. Or, to put it simply, we reach the beginning of an abyss separating earth from heaven — and us from God. A bridge is needed so that we may pass over to the other side.

The period of the Old Covenant thus begins the initial stages of the greatest bridge-building project the world has ever seen. It was a work accomplished on a grand scale by Christ — the bridge that we cross on our way through the Easter Mystery. Pontifex means “bridge builder,” and so Jesus is called. But He’s not just any bridge builder, but the greatest builder of all times: He is the Pontifex Maximus.

The first great preparatory event for the Paschal Mystery, the bridge to heaven, occurs in Egypt. In fact, the entire Exodus account includes a series of events foreshadowing Christ’s passing over from life to death and from death to new life. For some four hundred years, the Chosen People, having once lived in honor, now reside in slavery. Hearing their cries and showing mercy on His people, whom He calls collectively His “firstborn son” (Exod. 4:22), God sends a series of plagues upon the land until, begrudgingly, Pharaoh sends the Chosen People away. In a sense, these plagues set the table for the Paschal Mystery. For, at the doorstep of their passage out of Egypt, the Israelites celebrate the first Passover ritual (an account read annually during the Liturgy of the Word at the Mass of the Lord’s Supper). For this meal, a year-old, unblemished lamb is slaughtered. Its blood is painted around the doors of the Israelites’ homes, and its flesh is eaten during the night, in the house, with unleavened bread. The Lord describes what will happen next:

This is how you are to eat it: with your loins girt, sandals on your feet and your staff in hand, you shall eat like those who are in flight. It is the Passover of the Lord. For on this same night I will go through Egypt, striking down every firstborn of the land, both man and beast, and executing judgment on all the gods of Egypt — I, the Lord! But the blood will mark the houses where you are. Seeing the blood, I will pass over you; thus, when I strike the land of Egypt, no destructive blow will come upon you.

That night, the Israelites left Egypt. After the Lord had passed over their homes, they would take a journey that led them to another kind of passover. With the Egyptians at their heels (since Pharaoh had changed his mind about releasing the Chosen People), and led by a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night (Exod. 13:21), God’s children reach that great gulf between their old life in Egypt and a new life in the Promised Land — the Red Sea. But as the Israelites stand on the seashore, salvation history’s first paschal bridge appears before them, with Moses at its head: “Tell the Israelites to go forward. And you, lift up your staff and, with hand outstretched over the sea, split the sea in two, that the Israelites may pass through it on dry land” (Exod. 14:15–16). This account from the book of Exodus, read each year at the Easter Vigil, anticipates what Jesus will do for us: lead us on a great crossing, a passage over a bridge from death to life, slavery to freedom, darkness to light.

The Exodus story presents perhaps the most prominent Old Testament account of the Paschal Mystery, but once the Jews experience this first Passover, the paschal motif starts appearing on a regular basis in salvation history. Consider the passage into the Promised Land after forty years of desert wandering. The Israelites are still east of the Promised Land in the territory called Moab, separated from their new home by the Jordan River. It sounds like a familiar predicament for God’s people, and God’s response is equally so. Recalling the great work He performed for His people in the Exodus account, “the Lord, your God, dried up the waters of the Jordan in front of you until you crossed over, just as the Lord, your God, had done at the Red Sea, drying it up in front of us until we crossed over” (Josh. 4:22–23). A later passover finds the great Old Testament heroines Naomi and Ruth journeying from Moab, a country afflicted with famine, to the rich harvest lands of Bethlehem in the springtime of the year (that is, during the time of the Passover ritual) in order to find abundant food and life in the bountiful fields of Boaz (see Ruth 1–2). Here again, the journey from suffering to abundant life involves the passage through a body of water, the Jordan River, which separates Moab from the Promised Land. The prophet Elijah also finds passage through water — building a bridge, like Moses, with the Lord’s help. While journeying with his disciple, Elisha, Elijah was taken up into heaven by a fiery chariot only after he “took his mantle, rolled it up and struck the water [of the Jordan River]: it divided, and the two of them crossed over on dry ground” (2 Kings 2:8).

The above passages from death to life through water are preparations and prefigurements for history’s greatest Passover, that of Jesus. Indeed, it is noteworthy that at Jesus’ Transfiguration atop Mount Tabor, He appears with Moses and Elijah. These two Old Covenant bridge builders serve as significant witnesses to the work Jesus is about to undertake, the “exodus that he was going to accomplish in Jerusalem” (Luke 9:31): His Passion, Death, and Resurrection.

We see the first steps of Jesus’ earthly passover in the Gospel of John. Here, while visiting the Temple during the feast of the Dedication, Jesus definitively proclaims that He is the Messiah.

Answering the question about His identity, Jesus announces, “The Father and I are one” (John 10:30). The Jews, enraged at His answer, reply, “You, a man, are making yourself God.” To this, Jesus replies, not without relevance to our current chapter, “Is it not written in your law, ‘I said, You are gods?’ ” (John 10:33–34). Then Jesus “escaped from their power. He went back across the Jordan to the place where John first baptized, and there he remained” (John 10:39 40). After crossing to the east side of the Jordan, Jesus will then retrace the steps of the Israelites so that He, too, may cross back over the Jordan, in a renewal of that original entrance into the Promised Land. Reaching the heart of the Promised Land — that is, Jerusalem — He will suffer, die, rise, and ascend back to the Father. Like Moses and Elijah before Him, Jesus is building a bridge; but unlike the old bridges, which were Ash Wednesday and Lent mere shadows, Christ’s bridge is the reality of the New Covenant. With His Resurrection, His bridge is built — and built to last.

In the texts examined so far in this chapter, we see how the Paschal Mystery stands at the center of salvation history. Original sin and personal sin cause chaos and separate us from God. Throughout the Old Testament, God prepares His people for the reunion of heaven and earth, so that we and all of creation can cross over from wilderness wandering into a land flowing with milk and honey. Jesus is history’s Greatest Bridge Builder, the Pontifex Maximus, who, through His Paschal Mystery, definitively rejoins fallen earth to glorious heaven. The building and crossing of the paschal bridge is the goal of Lent, the purpose of the Triduum, the glory of Easter.

Now that we’re properly oriented — provided with compass and map, as it were — let us go back to the beginning, to the dust from which Adam was formed, the dust we meet every year on an otherwise ordinary Wednesday in late winter. Let us consider how this Wednesday — Ash Wednesday — and the Lent that follows it offer us our first guidepost, directing our passover to Easter, a day on which all things will be made new.

Dust and ashes are distinguishing marks of Lent’s opening days. It is no accident that the Ash Wednesday service is one of the most popular Lenten observances, even for non-Catholics. Even for the nominally religious, ashes on the forehead contain a certain symbolic appeal, speaking not only of our origins but of our end. For, as ashes are placed upon our heads, we hear the words, “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” But Ash Wednesday is only the first step. As we go “Repent, and believe in the Gospel” is another formula given in the Roman Missal. A Devotional Journey into The Easter Mystery deeper into Lent, the liturgy further sharpens this focus on our ultimate destination. On the Sunday following Ash Wednesday, the First Reading presents the creation account, which takes us even further back to our dusty roots in the Garden of Eden. Here we read how “the Lord God formed the man out of the dust of the ground and blew into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being” (Gen. 2:7). We were made from dust, and with the Fall we descend back into dust. We are reminded of this fact of life (and death) in the Ash Wednesday blessing over the ashes, when we “acknowledge we are but ashes and shall return to dust.”

But the ashes do more than recall our own fall: they should remind us that our transgression has turned the entire cosmos to chaos. We have brought down not just ourselves but all of creation with us. Not long after Adam and Eve’s creation, “out of the ground the Lord God made grow every tree that was delightful to look at and good for food, with the tree of life in the middle of the garden” (Gen. 2:9). But with Adam’s sin (the name Adam means “earth” or “ground”), all of the ground is cursed (Gen. 3:17), as well as the vegetation that comes from it. It is fitting, then, that Ash Wednesday’s ashes are “made from the olive branches or branches of other trees that were Sunday readings occur on a three-year cycle (with the years designated by A, B, and C) and thus vary from year to year. Since the readings selected by the Church for the A cycle are especially sacramental and initiatory in character, however, these may be used each year, especially when a parish prepares candidates to receive the Sacraments of Initiation (baptism, confirmation, and the Eucharist) at the Easter Vigil. Earth’s trees and plants that were once alive are themselves reduced to dust, as an anticipation of our own death.

So, Ash Wednesday and Lent, especially its early weeks, remind us (can we forget?) that we humans (human, like Adam, means “earthly”) are given life from the ground by God’s will, but that we shall return to the ground by the free choice of our will. Thus far, not a happy story. But at least there is nowhere to go but up.

But listen to the first words on the Church’s Lenten lips. The entrance antiphon for Ash Wednesday declares, “You are merciful to all, O Lord, and despise nothing that you have made. You overlook people’s sins, to bring them to repentance, and you spare them, for you are the Lord our God” (Wis. 11:24, 25, 26). True, we have reduced ourselves to dust, but this is not where the story ends (how sad for those who believe it is!). God’s mercy, as Lent’s first proclamation says, overlooks the chasm of our sins and restores us to life. As the psalmist puts it: “He raises the needy from the dust, lifts the poor from the ash heap, Seats them with princes, the princes of the people” (Ps. 113:7-8). If creation raised us from the dust, and original sin returned us to dust, Lent and Easter will raise us up once more and bring us across that bridge that separates us from God.

But passing over has never been an easy task. Moses found the work exhausting (“If this is the way you will deal with me,” he complained to God, “then please do me the favor of killing me at once, so that I need no longer face my distress!” [Num. 11:15]). Joshua, who led the people into the promised land after Moses’ death, also knew the difficulty involved in passing over.

Recall how he and Caleb encouraged the frightened people to enter the Promised Land: “If the Lord is pleased with us, he will bring us in to this land and give it to us, a land which flows with milk and honey. Only do not rebel against the Lord! You need not be afraid of the people of the land, for they are but food for us!” (Num. 14:8–9). Similarly, both Elijah and Ruth passed over to new life only by great effort and toil. Consider the anguished pleas of Elisha before Elijah, and Orpah and Ruth before Naomi, prior to their respective passovers (see 2 Kings 2; Ruth 1). Anyone who has ever prayed the Stations of the Cross knows, too, that the same exertions (and more!) accompanied Jesus’ Passover (perhaps this is why both Moses and Elijah appear with Jesus at His Transfiguration — to give Him encouragement). The same challenge, too, opens before us in Lent.

Conclusion

The Church likens the Lenten season to climbing “the Holy mountain of Easter.” On the far side of the paschal bridge, from the vantage point of the Easter victory, the Church looks back on Christ’s (and our) work and calls it a “stupendous combat,” where death and life fought a bitter battle. It’s a battle worth fighting, and a battle we can win. But part of our success sees the goal, the end, the purpose: the Paschal Mystery, where we work Jesus to span heaven and earth. And unless there is a bridge in our sights on Ash Wednesday, our journey through Lent risks ending where we began: right here in the fallen and dusty world of sin. It is a good thing we have a captain, coworkers, and tools necessary to win to victory. It’s to these Lenten helps and supports that we will look in the next chapter.

+

This article is adapted from a chapter in A Devotional Journey Into the Easter Mystery by Christopher Carstens which is available from Sophia Institute Press.

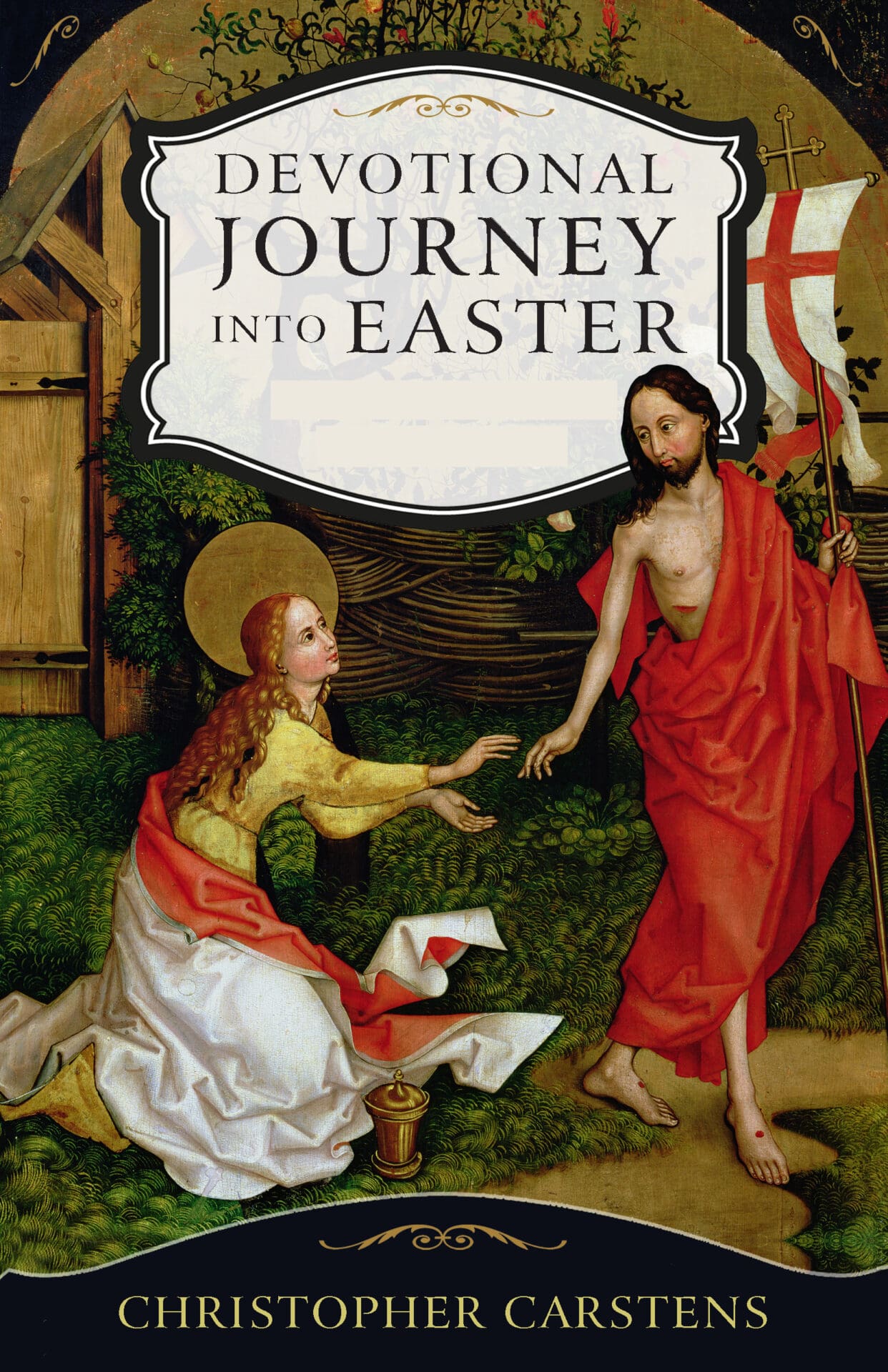

Art for this post on Lent: Cover and featured image used with permission.