Editor’s note: Connie Rossini continues her explanation of the new documents from the bishops of Spain on Christian prayer. Please see the first part here.

Last time, we began exploring the new document published by Spain’s bishops, My Soul Thirsts for God, for the Living God: Doctrinal Orientations on Christian Prayer. Today we begin to dig into the heart of the document.

The bishops note that people often ask them about authentic Catholic spirituality as opposed to Eastern meditation techniques. We read: “We want to offer criteria to discern which elements of other widespread religious traditions can be integrated into a Christian praxis of prayer to aid ecclesial institutions and groups to provide paths of spirituality with a well-defined Christian identity, responding to this pastoral challenge with creativity and, at the same time, with fidelity to the richness and depth of the Christian tradition” (no. 6).

They remind us of the adage, lex orandi, lex credendi, which translates roughly as “the Church believes as she prays.” If we are to maintain our faith in this post-Christian culture, and help others to do so as well, it is vital that we pray as Christians. Indulging in practices from other religions – no matter what our intent – may distort our views of God, the human person, and the goal of life. We cannot just co-opt practices from other traditions.

Certain theological truths underlie all Christian prayer. The bishops highlight the uniqueness of the Incarnation. Jesus alone is both fully God and fully man. Thus, any spirituality or spiritual practice that minimizes his role, making him into simply an example of how we all have the divine within us, is opposed to Christianity. The bishops also reject the idea that we cannot know the truth about God. Jesus came to reveal God to us. He is the one way to God. He and his words are truth.

Finally, they write, “It is important to note that in our culture, the Christian idea of salvation has been replaced by the desire of immanent forms of happiness, material welfare, and the progress of humanity” (no. 10). We will ultimately find these things to be empty. When that emptiness yawns before us, it’s easy to instead look for happiness in personal wellness. Then our focus turns inward, instead of outward to God. We become concerned with self, rather than the other. This danger, as we will see, is present in all forms of Eastern (non-Christian) meditation.

In reading documents like this, I sometimes long to see a list of problematic practices. It would make discernment and teaching about prayer so much easier! But the bishops of Spain, like the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in On Some Aspects of Christian Meditation, give us instead principles by which to judge whether a given practice is compatible with Christian prayer. Thus, they teach us about authentic Christian prayer at the same time that they warn against error. They account for new practices that may arise in the future. They expect us to examine prayer and meditation practices in light of these principles.

And yet, they did decide to focus in on perhaps the biggest current fad in both secular and Christian circles respecting meditation: mindfulness. Next time, we’ll look at their teaching on what they call “Zen Buddhism methodology” in general, and mindfulness most specifically.

For further exploration of topics discussed in this post, we recommend these books:

- A Catholic Guide to Mindfulness by Susan Brinkman using this link: https://amzn.to/34pvrJV

- Is Centering Prayer Catholic by Connie Rossini using this link: https://amzn.to/2Wq0ZMV

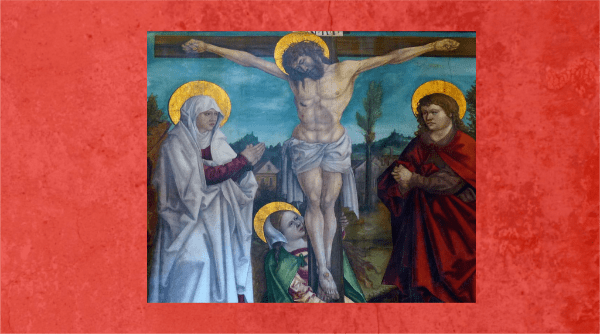

Image credit: Torun Regional Museum [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons