Editor’s Note: David Torkington continues his series with a segue into the history of Christian Mystical Tradition, looking now at how many saints anchored Christian spirituality and prayer in the person of Christ even in the most hostile, tumultuous times. To read part 33, see here. To begin with part 1, see here.

A Brief History of Christian Mystical Spirituality, Continued

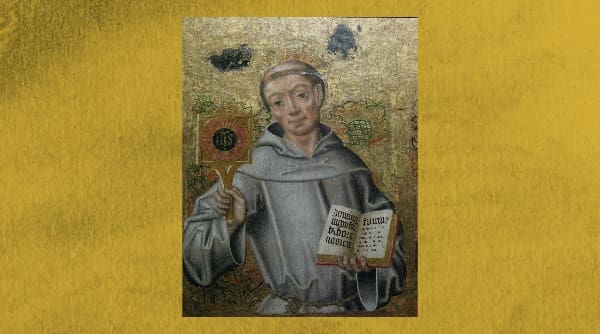

If you visit Italy you will see the famous monograms representing the Holy Name of Jesus designed by St. Bernadine. These monograms can be seen in churches, but also on public buildings, private houses and on wayside shrines. It was the badge of his new reform with the person of Jesus at its center. Learning to love him as Bernadine did in his solitude, was the way into the mystic way, into the mystical body and into Christ’s loving contemplation of Infinite Love, our ultimate destiny. This is how he tried to convert ordinary people to the principle of the ‘primacy of love’ revealed to St. Francis—by leading them to the person in whom that love is generated. If St. Francis was called the ‘Second Christ’ by his contemporaries and treated as such, then St. Bernadine was treated likewise.

Contemplation and Reform

Tens of thousands came to listen to St. Bernadine and hundreds of young men moved by his example came to join his reform, hence all the new hermitages that were built to receive them. It was here they were taught the primacy of love by those who traveled before them on the mystic way. Here their love would be purified and refined, enabling their love to mix and merge with the love of Christ, opening them to the fruits of contemplation and preparing them to preach the new reform. St. Bernadine was not alone, he was joined by other great saints like St. John Capistrano, St. James of the Marches and Blessed Albert of Sarteano. The reform that spread all over Europe was not just through the Franciscans but through other orders too. The Benedictines are a good example of monks who were influenced by the reform. One monastery in Spain is of particular interest because it was at the monastery of Montserrat in Catalonia that something destined to have enormous significance for the future took place.

Introducing the Printing Press and St. Ignatius

The Abbot Garcias de Cisneros (1455-1510) was not only won over to the new reform but to the latest piece of new technology, the printing press. It was he who conceived the idea of printing what he called ‘spiritual exercises’ or instructions on how to meditate on the Christ, the center and inspiration of the new reform. These exercises spread far and wide for two reasons. The first was because Montserrat was one of the most popular places of pilgrimage in Spain as the shrine of Our Lady of Montserrat. Secondly, it was after returning from such a pilgrimage that St. Ignatius wrote his own ‘spiritual exercises’ while living for almost a year in a cave near the town of Manresa, not far from the famous monastery (1523-24). Thanks to the latest technology and St. Ignatius of Loyola, the centrality of the person of Christ in Christian spirituality would be assured for centuries to come, not enshrined in a theological treatise, but in a practical method of prayer that taught people how to come to know and love the person of Christ, making his presence pivotal in one’s whole life.

Not surprisingly, St. Ignatius would write in his diary that he wished to emulate St. Francis more than any other saint, nor was it therefore surprising that he should call his new order – The Society of Jesus. Other orders also initiated reforms too, like the Dominicans under Raymond of Capua who was inspired by St. Catherine of Siena. I will leave the Carmelite reform until later, as the fruits of their contemplation will be pivotal when I detail the journey ahead in the mystic way. Before moving ahead I must mention the reforms that were taking place in the Netherlands.

The Devotio Moderna and Thomas a Kempis

The name given to the best-known expression of their spirituality was the Devotio Moderna. It emphasized a personal piety full of feeling and sentiment that made Jesus a friend and personal savior. It was particularly associated with a certain Geert Groote and the ‘Brethren of the Common Life’. Most of us are familiar with it thanks to a member of that community, Thomas a Kempis, and his book, The Imitation of Christ, one of the bestselling religious books of all time.

While their fellow reformers in the South tended to make use of the spoken word, the northern reformers made good use of the written word and of the new printing presses that were coming into use almost everywhere. A new type of literature was beginning to have a deep influence on the faithful: books telling the life story of Jesus. Perhaps the most famous and the most popular was written by Ludolph the Carthusian and published in 1470, the Vita Christi (Life of Christ). This book had a lasting effect on St. Ignatius and on very many others too.

Pre-Tridentine Spirituality

These reforms sweeping across Europe in the century leading up to the Reformation should put to bed the later protestant assertion that the Catholic spirituality was in a state of ‘terminal decline’ prior to Martin Luther hammering his 95 articles to the door of the church in Wurttemberg in 1517. In his book, The Stripping of the Altars, Dr. Eamon Duffy has shown how among ordinary people the faith was alive and well. I hope, from what little I have written, I have been able to show that it was alive and well among most religious orders too, on whom the laity depended for leadership.

The popular devotional prayer known as the Jesus Psalter that endlessly repeated the name of Jesus was used perhaps more than any other form of prayer by the Recusants in England, who remained loyal to the Church, and the prayer to Jesus was the last prayer that many of the martyrs made as they were being brutally put to death at Tyburn and elsewhere.

The truth of the matter is that although there was more than enough depravity in high places thanks to the Renaissance Popes, particularly Alexander VI, on ground level the Franciscan reform movement was still bearing fruit. The Council of Trent (1545-1563) was not primarily called to combat spiritual degeneration, but Protestant heresies, and was preceded by great saints like St. Catherine of Genoa, St. Angela Merici, St. Teresa of Avila, St. Peter of Alcantara, St. Ignatius, St. Philip Neri and so many others. While older orders were reformed, new orders were raised up to embody and disseminate the spirit and the teaching of the Council.

Post-Tridentine Spirituality

Orders like the Jesuits, Barnabites, Theatines, Capuchins, Discalced Carmelites, and Oratorians were theologically and spiritually inspired and guided after the Council by such goliaths as St. Robert Bellarmine, St. Francis de Sales, St.Vincent de Paul, and St. John of the Cross. In the hands of such great leaders as these, for more than a hundred years after that Council, spirituality continued to thrive and prosper, surcharged from within by the profound mystical prayer that animated and inspired the Church since the great St. Bernard. In his life’s work, Enthusiasm, Monsignor Ronald Knox makes it quite clear:

“The seventeenth century was a century of mystics. The doctrine of the interior life was far better publicized, developed in far greater detail than it had ever been in late-medieval Germany or late-medieval England. Bremond, in his Histoire littéraire du sentiment religieux en France, has traced unforgettably the progress of that movement in France. But Spain too, the country of St. Teresa and St. John of the Cross, had her mystics, Italy also had her mystics, who flourished under the aegis of the Vatican. Even the exiled Church in England produced in Father Baker’s Sancta Sophia a classic of the interior life” (Chapter XI).

In his unique and masterly work, The Spiritual Life – A Treatise on Ascetical and Mystical Life, Father Tanquerey admits that he is deeply indebted to the spirituality of the French school of the seventeenth century in which mystical theology reached such an advanced stage of development.

However, the clouds were beginning to gather. From small beginnings, a pernicious heresy was brewing that was going to do for the mystical life what Arianism did for the Christian life in earlier centuries. The heresy would be called Quietism, the movement that promises the Prayer of Quiet to those who have not been prepared to undergo the inner purification that would enable them to receive it.

More on this topic must be said if we are to see and understand why it was put down so vigorously and how it resulted in the demise of true Catholic Mystical spirituality of which so few are aware, with the catastrophic consequences for the Church down to the present day.

Art for this post: 16th-century painting of St. Bernadine in Langeais Castle, France, by unknown painter, Wikimedia Commons.