Mini-Course on Prayer

Section 2 Christian Meditation

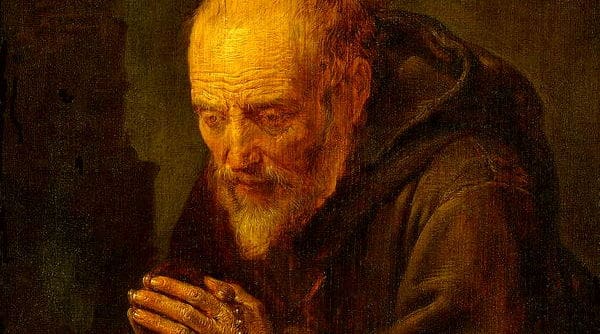

Part 15 -A Hermit at Prayer

Editor’s Note: In part 14, David Torkington discussed Mystical Premonitions. Today, he shares the wisdom of a hermit on the importance of silence and how to meditate on the Gospels.

In the following example of a hermit at prayer you can see how traditional meditation comes to its high point in silence. It is here when contemplating some of the most profound texts in the Gospels that a person is led on beyond words to savour something of the height and depth, the length and breadth of God’s love that surpasses the understanding. But let us listen to the hermit himself as he answers the questions of a young novice.

“How do you advise people to use the scriptures for meditation?” a young novice asked the hermit.

The hermit replied. “I advise them to turn to St John’s Gospel and most particularly to the discourse at the Last Supper, reading some of the texts several times, pausing over them, repeating them and asking God’s help to enable them to penetrate their meaning to allow the impact of that meaning to burst into their consciousness.”

His Words Had a Hypnotic Effect

The hermit stopped talking, sat back in his chair and closed his eyes remaining silent and quite motionless for a good thirty seconds before he began to speak. He began by drawing together several texts, repeating them slowly, unconsciously injecting into them a meaning born of long years of personal prayer.

“No one can come to the Father except through me. If you know me, you know my Father too. Do you not believe that I am in the Father and the Father is in me? Anyone who loves me will be loved by my Father and I shall love him and reveal myself to him. Make your home in me, as I make mine in you. Separated from me, you have no power to do anything.”

The hermit was able to put such depth of meaning into the words that it had an almost hypnotic effect on the novice who closed his eyes and a deep stillness came over him. The hermit paused before repeating the texts again, more slowly this time. When he repeated them for the third time the novice no longer noticed the way in which he delivered them, but their meaning bore in upon him with an impact that he had never before experienced. Somehow he needed the long pause that the hermit left after the final repetition to mull over the content of the texts. They had come alive for him in a new way. Then the hermit began to pray in words which were in complete accord with the novice’s own feelings. “Lord, I believe,” he prayed. “Help my unbelief.”

He made this prayer three times, lapsing again into silence. When he spoke again it was to use words of praise, thanks, and adoration. After another lengthy pause, he began to repeat individual phrases from the texts that he initially quoted.

“Make your home in me, as I make my home in you.” Then, after a short pause, “Separated from me, you have no power to do anything.” He repeated these two phrases several times, once again punctuated by pauses of varying lengths. A profound inner recollection came over the novice during the experience and it remained with him for the rest of the day.

The trouble is, we have to learn to listen. One of our problems is that we are bombarded with literature from all sides every day of our lives so that we have acquired a habit of reading at a breathtaking pace just to keep abreast of what is happening. Our only concern is to glean the relevant facts from what we are reading and to move on to something else. If we apply the same techniques to the way we read the Scriptures, then we will never come to know Christ more deeply. We should read the Scriptures as we would read good poetry, endlessly going over it to penetrate its content. People with an artistic temperament may like to use their imagination more fully in prayer, and they should be encouraged to do so.

Scene Setting

The novice asked the hermit to explain what he meant by saying that people with an artistic temperament may wish to use their imagination more fully in prayer. He explained how the imagination can be used to set the scene in detail before starting to listen to the words of Christ.

“For instance, for the short meditation we have just shared together, you may find it helpful to begin by recreating the scene of the Last Supper in your mind, picturing the Apostles preparing the table, seeing Jesus coming into the room, watching him move, looking at his face when he speaks, noting the expression. The same sort of scene-setting could be used to recreate the atmosphere before meditating on other Gospel texts. The Passion of Christ, for instance would lend itself to this method of praying. Do not just think of what Christ went through. Go back in your imagination and place yourself in the event. You are amongst the soldiers at the scourging, one of the crowd during the carrying of the Cross, an onlooker at the actual Crucifixion. You see everything as it happens; you open your ears and hear what is said, and then you open your mouth and begin to pray.”

“But isn’t that emotional approach out of date nowadays?” the novice asked.

“There is no such thing as an out-of-date method of prayer if it helps to recreate the profound meaning of the Gospels, and leads a person to come to know and love Christ more deeply,” said the hermit emphatically. “I know many people who could have made great headway with prayer if they had not rejected certain traditional methods of meditation because they thought they were old-fashioned. I do however know what you mean. Many meditation manuals, particularly in the last century made a nonsense out of this particular approach to prayer by writing oceans of pious sentimentality that made one feel ill at ease in their company. Certainly, this approach does not appeal to everybody, but it can be very helpful to some, and they should not be put off because it is not the ‘in fashion’.

The Passion is a Primary Source for Meditation

The Word was made Flesh so that people of flesh and blood could understand and see God’s love made tangible. Christ’s death was a brutal, bloody and painful event through which the ‘Word made Flesh’ speaks of love in a way that is intelligible to all. To neglect the Passion as a primary source of Christian meditation and prayer is to neglect the most important manifestation of God’s love that ever happened. We are not blocks, we are not stones, we are not senseless things. If we are afraid to be moved emotionally because it is not in fashion or not trendy, then we better start by praying for a little of the humility of the child, if we ever hope to enter into the Kingdom.

In addition to using the scriptures to read slowly and prayerfully to set our hearts alight with the love that leads to contemplation, turn to other sources too that have themselves been inspired by the scriptures. There are many profound and beautiful hymns that we only glance at briefly every now and then when we sing them in church; Hymns like ‘Lead, Kindly Light’, ‘Abide with Me’, ‘Rock of Ages’ or ‘Come, Holy Spirit’. The hymnal can be a rich source of material for us to use for meditation reading them slowly and prayerfully as we would read the scriptures The Liturgy itself is an endless source of food for meditation for us to use in this way. The ‘Gloria’ is an excellent example. I always recommend it to people because meditating on it a verse at a time immediately takes them out of themselves. The focal point of the prayer is God and his Glory, and this is the end of all prayer, and of our very existence. Use the Eucharistic prayers too in the same way. Read them slowly, meditate on the meaning of every sentence, every word, making a spiritual communion at the words of consecration. In this way you can, not only unite yourself with the community with whom you usually take part in the liturgy, but with every community taking part in the sacred mysteries all over the world. The Desert Fathers said that every hermitage should have only three walls. The third is like a window that is open to the world for whom hermits are called to pray in their solitude.

n the next article the novice asks the hermit about the emotional paralysis, that for him, like so many, prevents us from penetrating the profound mysteries of the faith as we would wish.

These ideas are developed further in my two major works on prayer – Wisdom from the Western Isles and Wisdom from the Christian Mystics, and Wisdom from Franciscan Italy that shows how deep contemplative prayer grows to perfection in the Life of St Francis of Assisi.

+

Art for this post: A Hermit Praying by Gerrit Dou (public domain), via Wikimedia Commons.