Dear Father John, I know more than a few people who are fallen-away Catholics. They make fun of the Church sometimes, or they make fun of me. But my question has to do with “Catholic guilt.” They mention this sometimes and smirk, like it’s some kind of inside joke on me. I am not sure what they mean by this, but I have a sense that it’s holding them back living their faith. I would like to be able to help them. Can you give me any direction?

Dear Father John, I know more than a few people who are fallen-away Catholics. They make fun of the Church sometimes, or they make fun of me. But my question has to do with “Catholic guilt.” They mention this sometimes and smirk, like it’s some kind of inside joke on me. I am not sure what they mean by this, but I have a sense that it’s holding them back living their faith. I would like to be able to help them. Can you give me any direction?

This is not uncommon, and I think your instinct is right; their joking about “Catholic guilt” may actually be a providential opportunity. I will share some thoughts, hoping that you can use them to spark a fruitful, healing conversation the next time one of your friends takes refuge behind this rhetorical shield.

A Critique of the Critique

Some people who have left the Church (actively or passively) use the concept of Catholic guilt to help justify their exit. They explain that as they grew up in the Catholic Church, they were constantly badgered about sin, and were taught that God is angry and vindictive, watching over our every move, just waiting for a chance to catch us doing wrong and condemn us. This negative view of God and religion stifled their spiritual growth, they go on to say. They didn’t think it was healthy, or fair, and they didn’t like it, so one Sunday they walked out the doors of their parish Church after Mass and simply didn’t come back.

In one sense, this evaluation of the Church’s view on sin is correct: the Catholic Church is energetically against sin. We believe that sin is real, destructive, and to be avoided at all costs. Jesus even said we should cut off our hand or gouge out our eye if they caused us to sin (see Mark 9:38-50). (By the way, he didn’t mean that literally – after all, how can our hand or eye “cause” us to sin? Sin is always a free choice of our will against God’s will, and those choices stem from our heart.) Sin is the number one enemy of God and the human race, and so it is also the number one enemy of each one of our lives, the biggest obstacle to the happiness and fulfillment we crave.

But the next part of the fallen away Catholic’s critique isn’t so obvious – the part about God being constantly angry and our spiritual lives being stunted by guilt. In fact, that critique comes from a misunderstanding of what the Church teaches about guilt. If we can have in our minds the right understanding of guilt, we may be able to avoid straying off the good path ourselves, and help our wandering brethren come back into friendship with Christ.

Good Guilt

Basically, there are two kinds of guilt: good guilt and bad guilt. To use a rather clumsy analogy, good guilt is like a spiritual nervous system. Our physical nervous system is designed (at least in part) to help us recognize and avoid physical danger. So, for example, when we touch a hot piece of metal, our immediate reaction is to pull away, so we don’t get burned or damaged by it. Or, to take another example, if smoke from a fire seeps into a room, we start finding it hard to breathe; we start coughing. These are signs from our physical nervous system that we better get out of that room before we suffocate. Imagine if your nervous system was malfunctioning, and it wasn’t able to warn you about these kinds of bodily threats – you would be in an extremely dangerous situation.

Well, good guilt, healthy guilt, performs this same function for our souls. Physical health is good for our bodies in the same way as moral health is good for our souls. And moral health means doing good actions and avoiding evil actions. If our conscience is in good condition, it will register guilt when we commit, or toy with committing, evil actions. That guilt is a warning against performing or persisting in evil actions, because committing evil strains or breaks our friendship with God and damages our interior peace and integrity, just as a hot piece of metal will damage our skin and breathing smoke will damage our lungs. In this sense, the Bible’s and the Church’s warnings against sin are not the expressions of an angry and vindictive God. On the contrary, they are a sign of God’s infinite love; he knows that committing evil, even though it sometimes appears to give us a short term benefit, is destructive, both for ourselves and for others.

In fact, the “punishment” for sin isn’t something that God adds on, the way a judge in a court of law sentences a criminal. Rather, it consists precisely in the pain and misery caused by the sin itself; it is the result of the sin – just as the child who plays with knives even when his parents warn him not to suffers pain and misery when he cuts himself. It would be a mean and selfish God that didn’t warn us about the destructive consequences of evil actions. But it is a good and wise God who has given us the gift of a conscience, which helps us experience good guilt to warn us against committing sins, and to move us to repent if we have committed them.

Bad Guilt

The second kind of guilt is bad guilt. This occurs when we feel guilty without having done anything wrong. This is the kind of unhealthy guilt that can stifle our spiritual and emotional maturity by leading to moral confusion. Unhealthy guilt makes us blame ourselves for things that are not blameworthy, or for things outside the purview of our responsibility. When we do that, we become emotionally and spiritually tangled up, almost paralyzed, because escape from this feeling of false guilt is impossible: we cannot be forgiven for something we were not responsible for, or for something that wasn’t a sin.

Bad guilt becomes like a cul-de-sac; we go round and round in our minds trying to find mercy and a fresh start, but we can’t. It drains our energy and inhibits us from growing in our friendship with God and others, because we don’t feel worthy of their love, and so we keep them at a distance.

Bad guilt can come from at least two sources. First, it can come from not distinguishing between sins and simple mistakes. For example, if I sincerely forget to send my mom a mother’s day card, I may have strong feelings of regret, but I shouldn’t feel morally guilty about it (even if she tries to make me feel guilty) – it was just a mistake, an oversight, not a morally evil act. If, on the other hand, I purposely avoid calling my mom on her birthday because I’m nursing resentment about something she said five years ago and I actually want to make her suffer, then I should to feel guilty; Christians honor their parents, they don’t hold grudges against them.

Second, bad guilt can result from experiencing a defective authority figure (authority figures are supposed to help form our consciences, our ability to identify moral good and evil). This happens often in families that go through a divorce. The pain and conflict between the parents inhibit them from giving proper love and discipline to the children. As a result, the children begin to feel responsible for the problems their parents are having; they blame themselves for the neglect they are experiencing.

Or take the example of an unhappy, angry priest who is in charge of teaching the faith to the children of his parish. Every week he rants and raves about how sinful and evil people are, and how painful the punishments of hell will be. He never speaks about the unlimited mercy of God, which is always ready to forgive us. He never speaks about the goodness of our heavenly Father, who has prepared a place for each one of us in heaven. He never speaks about the wonderful mission that each one of us has received in this life, a mission that only we can accomplish. Instead, he focuses over and over again, week after week, on the fires of hell and the selfish tendencies of our hearts, drilling into the children a lopsided and distorted conception of God, and of themselves. Over time, that can feed bad guilt, an unhealthy feeling of guilt simply for being alive, as if our existence itself were some kind of sin. Nothing is worse for our relationship with God than that. And if someone leaves the Catholic Church because of this kind of experience, it would be unwise, but understandable.

Seeking a Solution

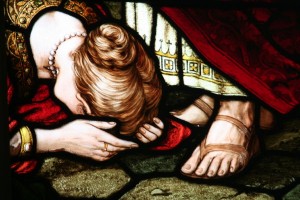

In either case, whether we are dealing with good guilt or bad guilt, the remedy is the same: returning to the loving embrace of God our Father and Christ our Lord. If we are experiencing good guilt, we need to repent and ask for forgiveness and mercy, which Jesus Christ won for us by suffering on the cross. God never runs out of mercy; he is always eager to dish it out. In fact, he invented the sacrament of confession in order to make dishing out his mercy as tangible a thing as possible. If we are experiencing bad guilt, then we need to go to God in prayer, reading and reflecting on the Bible, God’s own Word, which assures us, over and over again, that we are infinitely valuable in God’s eyes, that he is always thinking of us, that we have nothing to fear. Sin is real, and it matters; but God’s mercy is even more real, and it matters more. As the Catechism puts it, “The victory that Christ won over sin has given us greater blessings than those which sin had taken from us” (#420).

I pray that the next time a friend or acquaintance jibes you about Catholic guilt, these ideas will help you speak to them about what they really need to hear: the transforming power of Christ’s saving grace.

Yours in Christ, Father John Bartunek, LC