Dear Dan, I read your post on the Holy See’s concerns about Anthony de Mello, and I wondered as well about Thomas Merton. Some of his writings are helpful to me, but some make me very uncomfortable. Do you recommend his spiritual writings?

Dear Friend, I am grateful to hear you are investing so much energy into your spiritual reading. You will find immeasurable rewards in your efforts to continually delve into the great wealth of spiritual sustenance provided within the pure expression of our tradition.

With respect to Thomas Merton, there has been no official concern specifically expressed about his writings that I am aware of. However, the Vatican has specifically addressed the exploration of the integration of Eastern and Western faith systems (in which Merton was wholeheartedly engaged during the latter part of his life) in the following documents (well worth reading):

- Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on Some Aspects of Christian Meditation

- Jesus Christ the Bearer of the Water of Life

As well, on this site, Bishop Gregory Mansour wrote a few posts for us on spiritual direction, and in one of them he quotes Merton. At that time, I was aware of concerns about Merton, particularly from Alice Von Hildebrand and others. That said, I had also heard from others I respect who held Merton in high regard.

Since then, along with reading Merton, I have done a bit of research and have found one resource that is particularly fair and insightful on Merton. It was written by Anthony E. Clark for This Rock Magazine and titled, Can You Trust Thomas Merton? Clark is a Catholic author and professor of Chinese History and is uniquely qualified to address the issues that surfaced in Merton’s later writings. The bottom line is that there are two periods in Merton’s life and writings as categorized by Clark below (my headings).

The Early Period

These works represent the early era of Merton’s monastic life, when his views were still quite orthodox. These books are beautifully written; they are what made Thomas Merton Thomas Merton (note that this is Clark’s opinion, not mine. I give mine at the end of the post).

- The Seven Storey Mountain, 1948

- The Tears of the Blind Lions, 1949

- Waters of Siloe, 1949

- Seeds of Contemplation, 1949

- The Ascent to Truth, 1951

- Bread in the Wilderness, 1953

- The Sign of Jonas, 1953

- The Last of the Fathers, 1954

- No Man Is an Island, 1955

- The Living Bread, 1956

- The Silent Life, 1957

- Thoughts in Solitude, 1958

The Slip Into the East (Read with Caution)

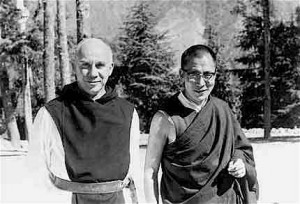

By 1966, Merton’s writings began to take an eastern turn toward Chinese and Japanese religious traditions. Starting with Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, his books begin to criticize the West and find answers in the East. Following are only a few examples of his more questionable works.

Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, 1966: Here Merton begins the part of his life that is critical of the West. While his criticisms of Western materialism and pragmatism ring loudly, especially in today’s world, one senses here a new interest in Eastern religion–and this is where his works become most problematic.

Mystics and Zen Masters, 1967: This is Merton’s first plunge into Eastern thought and religion. Its strength is its mostly cogent description of Chinese Daoism and Zen Buddhism, but one begins to discern Merton’s attitude shifting toward his later-developed notion that Eastern religion is a necessary supplement to Catholicism.

Zen and the Birds of Appetite, 1968: By now Merton is swimming in Zen–this work is a comparative consideration of Buddhism and Christianity. It’s beautifully expressed, but his overall goal is to erase the lines between two very distinct religious beliefs.

The Way of Chuang Tzu, 1969: This is one of Merton’s most problematic works. It valorizes the relativistic teachings of Zhuangzi, the Zhou dynasty Daoist. This is Merton’s final interweaving of Eastern and Western thought.

The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton, 1973: Here we find his final writings, and they are full of cathartic angst. At the end of this journal, one senses that Merton has knowingly wandered from clear Church teaching. While in Bankok, a Dutch abbot asked him to appear in a television interview, for “the good of the Church.” But Merton writes that, “It would be much ‘better for the Church’ if I refrained.”

My advice (Dan speaking now)? The Church is in no way lacking in solid and perfectly trustworthy writings on the spiritual life. I personally don’t know why anyone would want to carefully sift through this kind of literature when it is clear that Merton had serious moral issues even during the his “orthodox” period. It seems a bit like sifting through the refuse at the back of a good restaurant. You will no doubt find much that is of nutritional value, he was indeed a talented writer, but why not just go take your seat at the table for the best and purest meals available? I would encourage you to stick with the spiritual doctors of the Church. To name a few, the writings of St. Teresa of Avila, St. John of the Cross, St. Catherine of Siena and St. Francis de Sales will more than meet your needs for spiritual guidance and you need not worry that you might be led down a path that leads away from the Heart of the Church.

PS: I recognize that many have found that, through Merton’s writings, they have grown to more fully love and serve Christ. My thoughts here don’t in any way deny that reality or possibility. My intent here is to answer the question asked by the reader. The fact that God uses many means and instruments, including very flawed instruments, to lead people to Himself is assumed and appreciated in a very personal way.

Editor’s Note: Part II can be found here: Can I Trust Thomas Merton? (Part II of II)